Animal-Killing in Human Society

vanipedia.org/wiki/Animal-Killing in Human Society

Drawing upon information revealed in the Vedic literature, Śrīla Prabhupāda teaches that just as all human beings are embodied spirit-souls, equal in the eyes of the Lord, so too are animals. As such, he explains, the human being who kills an animal must be held morally responsible for that death under the laws of God and nature, much as one would be for the death of a human being. According to the Vedic instruction, he says, human society should protect the animal’s right to live.

Among the practical points Śrīla Prabhupāda discusses are recommendations for human diet and how human society can function successfully while avoiding (or at least restricting) the slaughter of animals. He includes information about exceptions and concessions that the Vedas allow for an animal to be killed, showing how such allowances are nonetheless also restrictions, as they are defined and limited by specific circumstances. Śrīla Prabhupāda teaches that the cow, above any other animal, is especially important to human society; for this reason the Vedas expressly forbid the killing of cows. Above all, Śrīla Prabhupāda argues that the systematic mass slaughter of animals, exemplified most grossly in modern slaughterhouse operations, cannot be justified on any grounds.

Śrīla Prabhupāda reminds his audience that regardless of what is acceptable according to human opinion or man-made law, the ultimate authority in the matter of animal-killing is God Himself. Thus he stresses that those who participate in the killing of animals outside the codes of God’s natural law must sooner or later suffer the karmic consequence of their actions. Śrīla Prabhupāda teaches that human civilization must be based upon correct knowledge of who we are as spirit-souls and what the aim of human life actually is; any society which allows for the unprincipled killing of animals, he argues, only serves to degrade itself and obstruct the real progress of humanity.

Śrīla Prabhupāda’s thought-provoking discussion of animal-killing introduces many fundamental teachings of the Vedas, underscoring the spiritual dimension of reality and the need to understand how life operates beyond the reach of mundane perception and limited, self-serving concepts. Practically as well as philosophically, his instruction touches upon other timely topics such as vegetarianism; sustainable and cruelty-free agriculture; war, violence and peace; human progress and degradation; and the right to life for all embodied souls.

This Vanipedia page includes two parts. The first is an introductory article offering a glimpse into what and how Śrīla Prabhupāda taught on the issue of animal-killing during the course of his preaching activity through the 1960s and '70s. The second is an extensive collection of easily accessed reference links to Śrīla Prabhupāda's books, letters, and transcribed lectures and conversations as related to this topic.

Summary Article

(Go to References)

(Go to Related Articles)

Introduction

The act of killing is condemned by virtually every code of human ethics. Killing is allowed by law only under certain circumstances. For instance, one may kill a deadly assailant in self-defense, or one may kill an enemy soldier in battle, but one may not kill a man on the street for the purpose of taking the man's coat. There is always some restriction applied to the act of killing - at least the killing of a human being. What about the killing of animals?

Śrīla Prabhupāda teaches that animals as well as human beings should be afforded the right to live, and that animal-killing in human society should be restricted to a very limited set of circumstances. The unnecessary killing of animals, he declares, is a core vice of human society – one of what he refers to as the four pillars of sinful life.

It is said in the śāstra, striyaḥ sūnā pānaṁ dyūtaṁ yatrādharmaś catur-vidhāḥ: "Four kinds of sinful activities: illicit sex life, striyaḥ; sūnā, the animal slaughter; pānam, intoxication; dyūtam, gambling." These are the four pillars of sinful life.[1]

Sūnā means unnecessarily killing the animals. Just like slaughterhouse. You cannot maintain slaughterhouse in the human society and at the same time you want peace. It is not possible... this practice, unnecessarily killing animal, is one of the pillar of sinful life.[2]

He reveals the link between human suffering and animal slaughter as it is widely practiced in contemporary society.

The pillars of sinful activities, that is also mentioned in the Bhāgavata. Striya-sūnā-pāna-dyūta yatra pāpaś catur-vidhāḥ: (SB 1.17.38) "Four kinds of sinful activities: illicit sex, and intoxication, and unnecessarily killing of animals, and gambling." All the slaughterhouses of the world are being maintained unnecessarily. That is recruiting simply sins. They are eating sins, and therefore the world is in trouble. Simply committing. There is no necessity of killing animals. But here in India they are killing ten thousand cows daily, what to speak of Western countries. So people are so much addicted to sinful activities. How they can be happy? They are condemned.[3]

Śrīla Prabhupāda further explains that unrestricted animal-killing is a key factor underpinning degradation in human society. Prohibiting the whimsical and unnecessary killing of animals, he teaches, is a basic principle of civilized life. The following article, sourced from the archived record of Śrīla Prabhupāda’s books, lectures, conversations and letters, presents a summary report of Śrīla Prabhupāda’s instruction regarding animal-killing and the proper treatment of animals on the part of human beings.

The embodied soul and natural law

Śrīla Prabhupāda's views on animal-killing are informed by Vedic teachings regarding the nature of the living entity, the condition of the living entity in the material world, the laws of nature ordained by the Supreme Lord, and the resultant ethical implications. This article begins with an overview of Śrīla Prabhupāda's explanation of key philosophical points he presents in connection with the issue of animal-killing in human society.

Animals as spirit souls

Śrīla Prabhupāda's instruction rests on the fundamental teaching that animals are spirit-souls, just as human beings are – encaged in material bodies of various types, but nonetheless each a part and parcel of God. The difference between the human being and the animal, he says, lies in their relative levels of consciousness, not in the presence or absence of the soul.

What is the symptom of possessing soul? First of all try to understand. That is explained in the Bhagavad-gītā: avināśi tu tad viddhi yena sarvam idaṁ tatam: (BG 2.17) The presence of soul can be perceived when there is consciousness on the body. This is the proof. When you pinch my body, I feel pain, when I pinch your body, you feel pain, when I pinch an animal's body, he also feels pain. Even I pinch even the tree's body he feels pain.[4]

They are also living beings. Of course, in some quarter they say that the cats and dogs and lower animals, they have no soul. No. That is not the fact. Everyone has got soul, but the cats and dogs and animals, they are not advanced in consciousness. As soon as there is soul, there must be consciousness. These things are described in the Bhagavad-gītā, and you can perceive also. I am existing in this body; you are existing in your body - how it is known? By the consciousness. If I pinch your body, you feel pain. You pinch my body; I feel pain. Similarly, cats and dogs, they also feel pain or pleasure. So that is the proof of existence of the soul even in cats and dogs and human beings. The only difference is in the human form of life the consciousness is developed. [5]

Śrīla Prabhupāda further cites evidence from Bhagavad-gītā 14.4, wherein Lord Kṛṣṇa declares:

- sarva-yoniṣu kaunteya

- mūrtayaḥ sambhavanti yāḥ

- tāsāṁ brahma mahad yonir

- ahaṁ bīja-pradaḥ pitā

- "It should be understood that all species of life, O son of Kuntī, are made possible by birth in this material nature, and that I am the seed-giving father."[6]

Śrīla Prabhupāda explains:

Sarva-yoniṣu, all different forms of life, there is soul, part and parcel of God... The animals may be less intelligent. A child may be less intelligent than the father; that does not mean there is no soul… Everyone has soul. That is real. We get it from Kṛṣṇa: sarva-yoniṣu. (BG 14.4) In different forms of life the soul is there, undoubtedly. That is real conception of soul.[7]

He additionally refers to Lord Kṛṣṇa's words in Bhagavad-gītā 5.18:

- vidyā-vinaya-sampanne

- brāhmaṇe gavi hastini

- śuni caiva śva-pāke ca

- paṇḍitāḥ sama-darśinaḥ

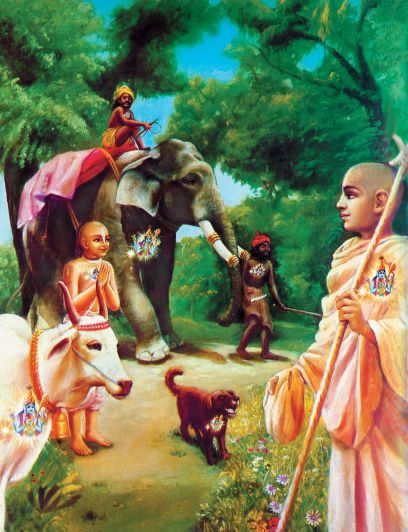

- "The humble sages, by virtue of true knowledge, see with equal vision a learned and gentle brāhmaṇa, a cow, an elephant, a dog and a dog-eater (outcaste)."[8]

Commenting on this verse, Śrīla Prabhupāda notes that one who is truly learned (paṇḍita) understands the presence of the soul as reality and sees the soul within the body of all living beings, regardless of external appearance.

Paṇḍita means learned, and he knows that "These Americans, these Europeans, these Africans or these Indians or these cows, these dogs and the elephant, trees, the plants, the fish - they have got different dress only, but the soul is the same. The living force within the body, that is the same particle, spiritual particle, part and parcel of the supreme spirit, Kṛṣṇa."[9]

In this way, Śrīla Prabhupāda establishes that the presence of the soul in all living beings is one premise on which any discussion of animal-killing must take place.

Transmigration, evolution and ahiṁsā

In addition to showing that the soul exists in lower animals as well as humans, Śrīla Prabhupāda explains how individual souls take on varieties of bodily forms in the material world and how this relates to the Vedic ethic of nonviolence toward all living beings.

Transmigration of the soul

The soul is described in Bhagavad-gītā (2.20):

- na jāyate mriyate vā kadācin

- nāyaṁ bhūtvā bhavitā vā na bhūyaḥ

- ajo nityaḥ śāśvato ‘yaṁ purāṇo

- na hanyate hanyamāne śarīre

- "For the soul there is neither birth nor death at any time. He has not come into being, does not come into being, and will not come into being. He is unborn, eternal, ever-existing and primeval. He is not slain when the body is slain."[10]

Śrīla Prabhupāda explains how the spirit-soul appears in the material world in different life forms:

Since the living entities are never annihilated, they simply transmigrate from one life form to another. Thus there is an evolution of forms according to the degree of developed consciousness. One experiences different degrees of consciousness in different forms. A dog's consciousness is different from a man's. Even within a species we find that a father's consciousness is different from his son's and that a child's consciousness is different from a youth's. Just as we find different forms, we find different states of consciousness. When we see different states of consciousness, we may take it for granted that the bodies are different. In other words, different types of bodies depend on different states of consciousness. This is also confirmed in the Bhagavad-gītā (8.6):

- yaṁ yaṁ vāpi smaran bhāvaṁ tyajanty ante kalevaram

- taṁ tam evaiti kaunteya sadā tad bhāva-bhāvitaḥ

"One's consciousness at the time of death determines one's type of body in the next life." This is the process of transmigration of the soul.[11]

While all souls are eternal, Śrīla Prabhupāda says, in the material world they inhabit various bodies as determined by God through the agency of material nature according to the qualities of their desires, their consciousness and their actions.

According to his karma, material activities, the spiritual spark attains a certain type of body. Material activities are carried out in goodness, passion and ignorance or a combination of these. According to the mixture of the modes of material nature, the living entity is awarded a particular type of body.[12]

The living entity changes his body as soon as the higher authorities decide on his next body. As long as a living entity is conditioned within this material world, he must take material bodies one after another. His next particular body is offered by the laws of nature, according to the actions and reactions of this life.[13]

In this life the mental condition changes in different ways, and the same living entity gets another body in the next life according to his desires. The mind, intelligence and false ego are always engaged in an attempt to dominate material nature. According to that subtle astral body, one attains a gross body to enjoy the objects of one's desires. According to the activities of the present body, one prepares another subtle body. And according to the subtle body, one attains another gross body. This is the process of material existence.[14]

Process of evolution

Śrīla Prabhupāda explains that there is also a process of evolution at work with the process of transmigration. In the following excerpt from his purport to Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam 4.29, he traces the general history of the incarnate soul:

Originally the living entity is a spiritual being, but when he actually desires to enjoy this material world, he comes down. From this verse we can understand that the living entity first accepts a body that is human in form, but gradually, due to his degraded activities, he falls into lower forms of life - into the animal, plant and aquatic forms. By the gradual process of evolution, the living entity again attains the body of a human being and is given another chance to get out of the process of transmigration. If he again misses his chance in the human form to understand his position, he is again placed in the cycle of birth and death in various types of bodies.[15]

Śrīla Prabhupāda shows that souls in the non-human forms of life follow an automatic path of progress up the evolutionary ladder until they reach a human incarnation, the pivotal point at which the soul is able to approach spiritual understanding and, at the highest level of realization, be liberated from the transmigration process. The advanced awareness and self-determination of the human being accounts for the superiority of the human over other forms of life.

The living entity's evolution through different types of bodies is conducted automatically by the laws of nature in bodies other than those of human beings. In other words, by the laws of nature (prakṛteḥ kriyamāṇāni (BG 3.27)) the living entity evolves from lower grades of life to the human form. Because of his developed consciousness, however, the human being must understand the constitutional position of the living entity and understand why he must accept a material body. This chance is given to him by nature, but if he nonetheless acts like an animal, what is the benefit of his human life? In this life one must select the goal of life and act accordingly.[16]

The individual soul is already under specific material nature, and the process is going on in lower grades of life, but in the human form of life, by advancement of education, one can become above the modes of material nature. That chance is given to him. This is stated in the Bhagavad-gita: "yanti deva vrata devan (BG 9.25)." So if he likes he can go back to Godhead, "yanti mad yajino 'pi mam," and stop this transmigration process...In the animal form there is no chance, only in the human form.[17]

The Vedic explanation of evolution differs from the currently popular theory offered by Charles Darwin. Whereas Darwin speculated on the presence and successive development of bodily forms solely in terms of gross physical factors, the Vedas reveal that it is the subtle factor of consciousness that determines bodily changes and the progress of the soul through various bodily forms. Śrīla Prabhupāda contrasts the Darwinian viewpoint to the Vedic understanding of the evolutionary process:

As stated in Brahma-vaivarta Purāṇa, there is a gradual evolutionary process, but it is not the body that is evolving. All the bodily forms are already there. It is the spiritual entity, or spiritual spark within the body, that is being promoted by the laws of nature under the supervision of superior authority. We can understand from this verse (Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam 4.24.73) that from the very beginning of creation different varieties of living entities were existing. It is not that some of them have become extinct. Everything is there; it is due to our lack of knowledge that we cannot see things in their proper perspective.[18]

One has to transmigrate from lower species of life, aquatic life, to trees; from trees to insect; insect to birds; birds to beasts; and from beasts, that is evolution. That evolution is not Darwin's evolution. That evolution, it is called janmānta vāda. The soul is going from one body to another, not that the body is transforming. The Darwin's theory is that the body is transforming. No. Body cannot transform. Body can take the shape according to the desire of the soul, or according to the effects, resultant action, of one's karma. The different types of bodies are all there.[19]

As Śrīla Prabhupāda points out, the soul that is now in an animal body will eventually, after serving time in various animal forms, attain a human form of body.

In the lower species of life there is an evolutionary process, and when the term of the living entity's imprisonment or punishment in the lower species is finished, he is again offered a human form and given a chance to decide for himself which way he should plan.[20]

Transmigration and ahiṁsā

Śrīla Prabhupāda explains how transmigration of the soul and the process of evolution relate to the killing of a living being:

All living entities have to fulfill a certain duration for being encaged in a particular type of material body. They have to finish the duration allotted a particular body before being promoted or evolved to another body. Killing an animal or any other living being simply places an impediment in the way of his completing his term of imprisonment in a certain body. One should therefore not kill bodies for one's sense gratification, for this will implicate one in sinful activity.[21]

He further illustrates:

Just like you are living in an apartment according to your position, but if I forcibly I ask you, "Go out of this apartment," then I will be punishable by the law. I have no right to get you out from that apartment. Similarly, every living entity by the laws of nature, all laws of nature, is imprisoned or allowed under certain apartment, either in the body of a tree or a human being or demigod or cat or dog. These are all ordained. So you cannot get out the living entity, soul, by force from that body. Then you will be punishable.[22]

This science underlies the Vedic ethic of nonviolence, ahiṁsā. Referring to the killing of an animal, Śrīla Prabhupāda explains:

Real ahiṁsā means not checking anyone's progressive life. The animals are also making progress in their evolutionary life by transmigrating from one category of animal life to another. If a particular animal is killed, then his progress is checked. If an animal is staying in a particular body for so many days or so many years and is untimely killed, then he has to come back again in that form of life to complete the remaining days in order to be promoted to another species of life. So their progress should not be checked simply to satisfy one's palate. This is called ahiṁsā.[23]

Right to live

Referring to Śrī Kṛṣṇa's statement in Bhagavad-gītā (14.4), Śrīla Prabhupāda emphasizes that Kṛṣṇa specifically says sarva-yoniṣu: all beings born of all species of life, from the lowest microbe to the highest form of human life, Kṛṣṇa personally declares to be His own.

Kṛṣṇa says that "I am the seed-giving father of all living entities in any form." Sarva-yoniṣu.(BG 14.4) Sarva means all, 8,400,000 species and forms. So Kṛṣṇa is the father, and all living entities are part and parcel of the Lord. They have different dresses according to different karma, but actually, every living entity is part and parcel of God, sons.[24]

Śrīla Prabhupāda explains that as children of the Supreme Father, all living entities are equal in His eyes and brothers on the spiritual level. Given this platform of understanding, the killing of an animal should be taken no less seriously than the killing of a human being.

So as there is state laws that you shall be killed if you kill your fellow man, similarly in the God's law there are the same thing. Not only man; if you kill anyone, then you'll have to suffer, because everyone is God's creature. They are in different dress only. He's considered the supreme father. So father may have many children - one is not very intelligent, another is very intelligent. And if the intelligent son says to the father that "This, my brother, is not intelligent. Let me kill him," will the father allow? Because his one son is not very intelligent, and if the intelligent son desires to kill him to avoid the burden, will the father agree to this? No. Similarly, if God is the supreme father, how He can sanction that you live and you kill animal? The animals are also His sons.[25]

Drawing on the authority of Śrī Īśopaniṣad (Mantra 1), Śrīla Prabhupāda states that each and every living being, as a member of the universal family of God, has the right to live at the cost of the Father.

The earth or any other planet or universe is the absolute property of the Lord. The living beings are certainly His parts and parcels, or sons, and thus every one of them has a right to live at the mercy of the Lord to execute his prescribed work. No one, therefore, can encroach upon the right of another individual man or animal without being so sanctioned by the Lord.[26]

If you make this world as belonging to the human society, that is defective. It belongs to everyone. It belongs to the trees community, it belongs to the beast community. They have got right to live. Why should you cut the trees? Why should you send the bulls to the slaughterhouse? This is injustice.[27]

Śrīla Prabhupāda relates this encroachment upon the rights of others to the concept of hiṁsa (or jīva-hiṁsa). He writes: "Jīva-hiṁsana refers to the killing of animals or to envy of other living entities. The killing of poor animals is undoubtedly due to envy of those animals."[28] As he explained to one of his disciples:

Envy means the cow has got right to live. He does not allow the cow to live. That is envy. You cannot understand this? Suppose you are walking. You have got right to walk, I have got, and if I kill you, you cannot walk. That is envious. Everyone has got right to live. Just like the camel. God has given their food. They are accustomed to eat these thorny twigs. So Kṛṣṇa has given that. Let them eat and live. Why should you interfere with his living condition?[29]

The principles of spiritual life prohibit acts of hiṁsā, including, as Śrīla Prabhupāda stresses, the unnecessary killing of animals.

Any circumstances, the direct killing is not approved by any śāstra, any religion. Jīva hiṁsā. Caitanya Mahāprabhu also says, niṣiddhācāra jīva-hiṁsā. So, jiva hiṁsā, violence upon other animals, that is against Vaiṣṇava principle. You cannot be violent, you cannot kill.[30]

You have got right to live and the lamb has got right to live. Why should you encroach upon his living right? Because you are strong. That is not humanity. The animal is therefore benefit. Let him live and you take the fur. You can use it for your coat, but why should you kill it? The cow is giving milk like mother, why should you kill it? This is humanity, to kill the mother? So in this way we are encroaching the rights of others, and we are becoming subject to be punished by God.[31]

(Go to references for "The embodied soul and natural law")

Culture of humanity

Śrīla Prabhupāda distinguishes the human being from lower animals by virtue of the naturally greater intellectual capacity and higher level of awareness that come with the human form of life. He shows that along with this superior position comes a greater degree of moral responsibility as well as freedom of choice. Śrīla Prabhupāda teaches that God and nature endow human beings with a unique chance to determine their own destiny by way of culturing knowledge and properly informed action, and that Vedic culture serves as a guide for achieving the real aim of human life - the uniquely human goals of spiritual realization and liberation from material existence. Real human culture, he says, means this culture: that which supports the progressive development of the human being in spiritual consciousness. The following section surveys Śrīla Prabhupāda's instruction regarding animal-killing as it relates to civilization and the culture of humanity.

Food for man?

Animal-killing is most frequently justified as a means to provide food for human beings. The bulk of Śrīla Prabhupāda's discussion of animal-killing centers on the slaughter of animals for food. Clearly, man is capable of slaughtering animals and consuming their flesh. But should he? Following the teachings of the Vedas, Śrīla Prabhupāda says no.

Jīvo jīvasya jīvanam

It is stated in Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam (SB 1.13.47):

- ahastāni sahastānām

- apadāni catuṣ-padām

- phalgūni tatra mahatāṁ

- jīvo jīvasya jīvanam

- "Those who are devoid of hands are prey for those who have hands; those devoid of legs are prey for the four-legged. The weak are the subsistence of the strong, and the general rule holds that one living being is food for another."[32]

It might appear that by virtue of this systematic law of subsistence, the killing of animals for food would be justified. However, as Śrīla Prabhupāda's comprehensive understanding of Vedic instruction shows, what God and nature intend for human beings is not automatically the same as what is set forth for other forms of life. This verse gives information about how the material world is arranged; it is not given as a positive guide for civilized human living. Śrīla Prabhupāda writes:

The living beings who have come to the material world against the will of the Supreme Being are under the control of a supreme power called māyā-śakti, the deputed agent of the Lord, and this daivī māyā is meant to pinch the conditioned souls by threefold miseries, one of which is explained here in this verse: the weak are the subsistence of the strong. No one is strong enough to protect himself from the onslaught of a stronger, and by the will of the Lord there are systematic categories of the weak, the stronger and the strongest. There is nothing to be lamented if a tiger eats a weaker animal, including a man, because that is the law of the Supreme Lord. But although the law states that a human being must subsist on another living being, there is the law of good sense also, for the human being is meant to obey the laws of the scriptures. This is impossible for other animals.[33]

In other words, the scriptures give laws for human living, and human beings are meant to follow those laws and not the laws of animal life. As Śrīla Prabhupāda writes in his purport to Śrī Īśopaniṣad (Mantra 1):

The standard of life for human beings cannot be applied to animals. The tiger does not eat rice and wheat or drink cow's milk, because he has been given food in the shape of animal flesh. Among the many animals and birds, some are vegetarian and others are carnivorous, but none of them transgress the laws of nature, which have been ordained by the will of the Lord. Animals, birds, reptiles and other lower life forms strictly adhere to the laws of nature; therefore there is no question of sin for them, nor are the Vedic instructions meant for them. Human life alone is a life of responsibility.[34]

Proper food for man

Although there are all kinds of eatables available in the world, not every creature eats every type of food. As Śrīla Prabhupāda explains, God provides all living beings with foods suited to their various natures; God has likewise supplied humans with their particular foodstuffs according to the purpose and design of human life, and these do not include flesh.

If you inquire, "Then why you restrict, "No meat-eating'?" The answer is that actually we do not make any distinction between the meat-eaters and the vegetable eaters, because the cow or the goat or the lamb has got life, and the grass, it has also got life. But we follow the Vedic instruction. What is that? Now, īśāvāsyam idaṁ sarvaṁ yat kiñcit jagatyāṁ jagat, tena tyaktena bhuñjīthā: (ISO 1) everything is the property of the Supreme Lord, and you can enjoy whatever is allotted to you. Mā gṛdhaḥ kasya svid dhanam. You cannot touch others' body, others' property. You cannot touch. That is Vedic life. So in all scriptures it is stated that man should live on fruits and vegetables. Their teeth are made in that way. They can eat very easily and digest. Although jīvo jīvasya jīvanam: one has to live by eating another living entity. Jīvo jīvasya... That is nature's law. So the vegetarian also eating another living entity. And the meat-eater, they're also eating another... But there is discretion. Discretion means that these things are made for human being. Just like fruits, flowers, vegetables, rice, grains, milk—the animals do not come to claim that "I shall eat this." No. It is meant for man.[35]

Discrimination required

Śrīla Prabhupāda notes that animals, whose behavior is restricted by bodily design and instinct, follow the laws of nature by default.

In the living entities lower than the human being, they follow the nature's way, their allotted food. Just like the tiger eats blood and flesh. If you offer him nice fruit, nice sweet rice, he'll not eat. Even the dog, they do not like the sweet rice or nice kachorī and sṛṅgara. You'll see. They cannot eat. If they eat, they will fall diseased.[36]

Human beings have their own allotment of foodstuff as well; however, human beings have greater capacity for choice than do animals in what they are able to take for food. As such, Śrīla Prabhupāda emphasizes that human beings must exercise their power of discretion when it comes to eating.

You cannot eat anything which is beyond the jurisdiction of your food. For you, for a human being, the food is, I mean to say, given there, quota, that "You can eat grains. You can eat fruits. You can eat flowers, vegetables. You can eat milk." That is sattvikāhāra, foodstuff prepared from vegetables, fruits, grains, sugar, and milk products. That's all. That is sattvika. That is allotted for the human being. You cannot imitate the cats and dogs: "Because they are eating meat, I also meat... Meat also is my food." They put forward, "Everything is food." So why don't you eat stool? That is also food - for the hog. So we must have discrimination, that what sort of food we shall take. Not that like hogs, anything will be accepted. That is humanity.[37]

Śrīla Prabhupāda concedes that a certain amount of violence must take place in order for any living entity to eat. From there, however, it becomes a matter of selection.

Discrimination is the better part of valor. Whom should we kill? It is all right. Jīvo jīvasya jīvanam. But there is important. If you eat vegetables there is no crisis, you can go on. It is a fact that an animal is eating another animal. It may be vegetables or animals, but they are disturbing. Therefore it is said, "As it is allotted." You should eat such and such. Not that indiscriminately you can eat everything.[38]

Sometimes the question is put before us: "You ask us not to eat meat, but you are eating vegetables. Do you think that is not violence?" The answer is that eating vegetables is violence, and vegetarians are also committing violence against other living entities because vegetables also have life. Nondevotees are killing cows, goats and so many other animals for eating purposes, and a devotee, who is vegetarian, is also killing. But here, significantly, it is stated that every living entity has to live by killing another entity; that is the law of nature. Jīvo jīvasya jīvanam: one living entity is the life for another living entity. But for a human being, that violence should be committed only as much as necessary.[39]

He notes that some foodstuffs can be procured without killing.

First of all, vegetables are not killed. If I take a fruit from the tree, the tree is not killed. Or if I take the grains from the plant, before the grains are ripe the plant dies. So actually there is no question of killing. Although the law is, nature's law is that "One living entity is the food for another living entity." Jīvo jīvasya jīvanam. But a human being should be discriminative. If I can live by eating fruits and grains and milk, why shall I kill animal?[40]

The only animal food meant for humans, he says, is milk, which may be obtained without violence as part of God's arrangement.

One should accept only those things that are set aside by the Lord as his quota. The cow, for instance, gives milk, but she does not drink that milk: she eats grass and straw, and her milk is designated as food for human beings. Such is the arrangement of the Lord.[41]

The verdict is that under most circumstances, for the human being to kill an animal for food is an act of unnecessary violence.

By the law of the Supreme Lord, all living beings, in whatever shape they may be, are the sons of the Lord, and no one has any right to kill another animal, unless it is so ordered by the codes of natural law. The tiger can kill a lower animal for his subsistence, but a man cannot kill an animal for his subsistence. That is the law of God, who has created the law that a living being subsists by eating another living being. Thus the vegetarians are also living by eating other living beings. Therefore, the law is that one should live only by eating specific living beings, as ordained by the law of God. The Īśopaniṣad directs that one should live by the direction of the Lord and not at one's sweet will. A man can subsist on varieties of grains, fruits and milk ordained by God, and there is no need of animal food, save and except in particular cases.[42]

Beyond vegetarianism

As Śrīla Prabhupāda explains, the exclusion of animal flesh from the human diet is not exactly a question of ‘vegetarian’ vs. ‘non-vegetarian.’ Beyond the consideration of material substance, he emphasizes that human beings should eat only those foods which have first been offered to the Supreme Lord (prasāda).

The human being is meant for self-realization, and for that purpose he is not to eat anything which is not first offered to the Lord. The Lord accepts from His devotee all kinds of food preparations made of vegetables, fruits, leaves and grains. Fruits, leaves and milk in different varieties can be offered to the Lord, and after the Lord accepts the foodstuff, the devotee can partake of the prasāda, by which all suffering in the struggle for existence will be gradually mitigated.[43]

Ultimately, it is for this reason that animal flesh is not recommended for human consumption: the Lord does not accept food offerings of animal flesh. Śrīla Prabhupāda gives the full purport of the Vedic instruction:

Animal killing is prohibited. Every living being, of course, has to eat something (jīvo jīvasya jīvanam). But one should be taught what kind of food one should take. Therefore the Īśopaniṣad instructs, tena tyaktena bhuñjīthāḥ: one should eat whatever is allotted for human beings (ISO 1). Kṛṣṇa says in Bhagavad-gītā (BG 9.26):

- patraṁ puṣpaṁ phalaṁ toyaṁ

- yo me bhaktyā prayacchati

- tad ahaṁ bhakty-upahṛtam

- aśnāmi prayatātmanaḥ

"If one offers Me with love and devotion a leaf, a flower, fruit or water, I will accept it." A devotee, therefore, does not eat anything that would require slaughterhouses for poor animals. Rather, devotees take prasāda of Kṛṣṇa (tena tyaktena bhuñjīthāḥ). Kṛṣṇa recommends that one give Him patraṁ puṣpaṁ phalaṁ toyam—a leaf, a flower, fruit or water (BG 9.26). Animal food is never recommended for human beings; instead, a human being is recommended to take prasāda, remnants of food left by Kṛṣṇa. Yajña-śiṣṭāśinaḥ santo mucyante sarva-kilbiṣaiḥ (BG 3.13). If one practices eating prasāda, even if there is some little sinful activity involved, one becomes free from the results of sinful acts.[44]

A question of yajña

Śrīla Prabhupāda stresses that the ideal human diet of prasāda is one which follows the wish of Lord Śrī Kṛṣṇa. The point is not nonviolence in itself, but rather the act of offering yajña, or sacrifice to please the Supreme Lord.

If Kṛṣṇa says that "Give Me meat," then we shall eat meat. Because we are concerned with Kṛṣṇa prasādam. We are not distinguished that "Vegetable eating is nice, meat eating is not nice." No. The nature's law is that you must eat, and that eating is something living. Vegetable is also living. But we are not concerned, vegetarian or nonvegetarian. We are concerned with Kṛṣṇa. Kṛṣṇa says, "You give Me fruits, flowers, grains." We offer that. If Kṛṣṇa says, "You give Me meat, chickens," we shall offer and we shall take.[45]

Even if we do not kill animals, simply by eating vegetables, they are also life... But our thing is that we have to offer yajña. Killing of animal does not mean that if a man kills a cow or goat for eating, he is killing, and those who are vegetarian, they are not killing. They are also killing. A vegetable has also got life. So it is not the question of killing. It is the question of offering yajña. It is the question of offering yajña.[46]

While Śrīla Prabhupāda advocates the topmost dietary recommendation, he also shows that the Vedas do not disallow flesh-eating entirely. He writes: "On the whole, meat-eating is not completely forbidden; a particular class of men is allowed to eat meat according to various circumstances and injunctions."[47] Some Vedic texts prescribe ritual sacrifices which help to mitigate the offense of killing an animal for food.

In the Vedic literature, even those who are meat-eaters, they are advised to sacrifice an animal before the deity Goddess Kālī, not purchased from the slaughterhouse. That is a kind of yajña, paśumedha-yajña. That is for low-class men. But still, because he's performing the yajña, he's less sinful.[48]

Procuring foodstuff

Regarding the law of subsistence and the culture of humanity, Śrīla Prabhupāda explains:

So this is the law of nature, that the weaker section is devoured by the stronger section... Therefore meat-eaters, so long they are like animals, they can go on with this nature's law. You are man, you are stronger; therefore weaker animal—cows and goats—you slaughter them. They are stronger bodily, but they have no intelligence. So man has got intelligence. So if you misuse your intelligence in that way, you can do that. That is nature's law. But human being means culture, advance, in spiritual consciousness. That is human.[49]

Nature's law of subsistence, he says, applies to animals and also to those humans who are unable to abide by higher instructions for human life. For human society, however, this law of subsistence should be taken as an exception rather than a rule.

One must eat something. The nature's law is that sahastānā... Sahastānām ahastāni. And catuṣ-padam. That is the arrangement by nature's way, that animals, they have no hands. So the primitive life, so they become food for the primitive natives or uncivilized man. They kill some animals and eat. And why civilized man do so? He can produce his food. God has given him land. He has intelligence.[50]

You have got sufficient grains, sufficient fruits, sufficient milk, milk products. Then if you can live on these things which are meant for human beings, why should you kill animals unnecessarily? If there is no alternative, that you cannot live... Just like in the desert, Arabian Desert, there is no food, no grain, for them animal-eating may be permissible. Because after all, we have to live. That is a different thing. But when you have got very nice foodstuff, and a very nutritious, palatable, sweet, why should you indulge in this unnecessary killing of animals? That is, will go against your purification. Therefore it is prohibited.[51]

In various ways Śrīla Prabhupāda argues that human culture means applying human intelligence and discrimination in the matter of procuring foodstuffs.

Then these animal killers, they may not be encouraged, "So then we are doing nice, because one living entity is food for another. So we are eating every, anything. Any moving animals we can eat. Bird, beast, goats, cows, horse, ass, whatever is available." Yes, you can eat. But that is the natural law for the animals and uncivilized man, not for the civilized man. Because one living entity is food for another living entity, you cannot eat your father, mother or children. Why? Because you are human being, you have got discrimination.[52]

We are eating milk, but we are not drinking the blood. Milk is nothing but blood of cow. But we know the art, how to drink the blood of cow without killing. That is civilization. That is civilization. Medically, they say the cow's blood or bull's blood is very effective, and that is accepted. But you must know the art.[53]

Śrīla Prabhupāda summarizes:

A tiger may eat meat. It is a tiger. But I am not tiger. I am human being... A tiger is made by nature's law in that way; therefore he can do that. You cannot do it. Your nature is different. You have got discrimination, you have got conscience, you are claiming civilized, human being. So you should utilize these things. That is Kṛṣṇa consciousness, perfect consciousness. So human life is meant for raising oneself to the perfection of consciousness, and that is Kṛṣṇa conscious. We cannot remain in tiger consciousness. That is not humanity.[54]

(Go to references for "Food for man?")

Cow protection and human civilization

According to Vedic culture, human beings should treat all animals with mercy and compassion. Above any other species, however, the cow is considered uniquely important to humanity. Śrīla Prabhupāda argues that the cow is an animal worthy of special protection because it supplies key products to support human culture. He speaks of the general economic value of the cow as a provider of foodstuff (in the form of milk) and materials (such as hide and bone) for footwear and various tools and instruments. Above this, he advocates cow protection as a bolster of higher-level civilization under the auspices of brahminical culture. In this regard he points to the special nutritional value of milk and the specific necessity of cow products for the performance of yajñas, religious sacrifices offered for the satisfaction of the Supreme Lord.

The cow and human society

Śrīla Prabhupāda explains that the human being has a special, beneficial relationship with the cow and that this relationship should be supported.

That is nature's way, by God's will, that a cow gives forty pounds, fifty pounds milk daily, but it does not drink. Although it is her milk, no, it gives you, human society: "You take. But don't kill me. Let me live. I am eating only grass." Just see... Without touching your foodstuff, the cow is eating the grass which is given by God, immense grass, and they are giving you the finest foodstuff, milk.[55]

Just like fruits, flowers, vegetables, rice, grains, milk - the animals do not come to claim that "I shall eat this." No. It is meant for man. Just like milk. Milk is an animal product. It is the blood of the cow changed only. But the milk is not drunk by the cow. She is delivering the milk, but she's not taking, because it is not allotted for it. By nature's way. So you have to take. Milk is made for man, so you take the milk. Let her live and supply you milk continually. Why should you kill? Follow nature's law. Then you'll be happy. Tena tyaktena bhuñjīthā (ISO 1). Whatever is allotted to you, take.[56]

Man can produce fruits and flowers, grains, take the substance, and the rejected portion give to the animal. She gives you milk. You require milk. This is cooperation.[57]

Śrīla Prabhupāda further notes that in the Vedic view, the cow and bull are seen as mother and father of society. Their service to human society is so vital that the Vedas specifically instruct the vaiśya class - the agricultural and commercial section of society - to give protection to these animals.

Lord Kṛṣṇa, as the teacher of human society, personally showed by His acts that the mercantile community, or the vaiśyas, should herd cows and bulls and thus give protection to the valuable animals. According to smṛti regulation, the cow is the mother and the bull the father of the human being. The cow is the mother because just as one sucks the breast of one's mother, human society takes cow's milk. Similarly, the bull is the father of human society because the father earns for the children just as the bull tills the ground to produce food grains. Human society will kill its spirit of life by killing the father and the mother.[58]

Supporting brahminical culture

Śrīla Prabhupāda presents cow protection, through its relation to brahminical culture, to be a basic principle of civilized life. He argues that brahminical culture must be present to guide human civilization in its purpose, which is to promote spiritual advancement (as well as material well-being) for the social body as a whole. Referring to the teachings of the Vedas, he indicates that cow protection and brahminical culture stand together as pillars of civilized society.

Śrīla Prabhupāda gives this succinct definition of brahminical culture:

Brahminical culture means the social position in which everyone is assisted to elevate himself to the highest position of understanding the position and the constitution of the soul. That should be the aim of human society.[59]

Commenting on a prayer from the Viṣṇu Purāṇa, he writes in one of his Bhagavad-gītā purports:

There is also a prayer in the Vedic literature that states:

- namo brahmaṇya-devāya

- go-brāhmaṇa-hitāya ca

- jagad-dhitāya kṛṣṇāya

- govindāya namo namaḥ

"My Lord, You are the well-wisher of the cows and the brāhmaṇas, and You are the well-wisher of the entire human society and world." (Viṣṇu Purāṇa 1.19.65) The purport is that special mention is given in that prayer for the protection of the cows and the brāhmaṇas. Brāhmaṇas are the symbol of spiritual education, and cows are the symbol of the most valuable food; these two living creatures, the brāhmaṇas and the cows, must be given all protection—that is real advancement of civilization.[60]

He further states:

The Lord is the protector of cows and the brahminical culture. A society devoid of cow protection and brahminical culture is not under the direct protection of the Lord, just as the prisoners in the jails are not under the protection of the king but under the protection of a severe agent of the king. Without cow protection and cultivation of the brahminical qualities in human society, at least for a section of the members of society, no human civilization can prosper at any length. [61]

Progressive human civilization is based on brahminical culture, God consciousness and protection of cows. All economic development of the state by trade, commerce, agriculture and industries must be fully utilized in relation to the above principles; otherwise all so-called economic development becomes a source of degradation. Cow protection means feeding the brahminical culture, which leads towards God consciousness, and thus perfection of human civilization is achieved.[62]

How does cow protection specifically relate to brahminical culture? As Śrīla Prabhupāda explains, cow protection supports brahminical culture by ensuring a good supply of milk products necessary for human nutrition and for essential religious observances.

Nutrition for humanity

Śrīla Prabhupāda wrote to one of his disciples: "Vedic civilization gives protection to all the living creatures, especially the cows, because they render such valuable service to the human society in the shape of milk, without which no one can become healthy and strong."[63] While he notes that all foods in the highest mode of nature (sattva-guna, or the quality of goodness) support health and human achievement by promoting sattvic qualities in those who consume them,[64] Śrīla Prabhupāda especially advocates milk as topmost among foodstuffs for its benefits to human life.

Human civilization means to advance the cause of brahminical culture, and to maintain it, cow protection is essential. There is a miracle in milk, for it contains all the necessary vitamins to sustain human physiological conditions for higher achievements. Brahminical culture can advance only when man is educated to develop the quality of goodness, and for this there is a prime necessity of food prepared with milk, fruits and grains.[65]

Milk, he explains, benefits individuals and society as a whole by promoting optimum development of the human brain.

If we really want to cultivate the human spirit in society we must have first-class intelligent men to guide the society, and to develop the finer tissues of our brains we must assimilate vitamin values from milk... No society can improve in transcendental knowledge without the guidance of such first-class men, and no brain can assimilate the subtle form of knowledge without fine brain tissues. For such important brain tissues we require a sufficient quantity of milk and milk preparations. Ultimately, we need to protect the cow to derive the highest benefit from this important animal. The protection of cows, therefore, is not merely a religious sentiment but a means to secure the highest benefit for human society.[66]

Śrīla Prabhupāda further states that milk is, in one way or another, an essential part of everyone's life.

So from the cows, the milk. And from the milk we can make hundreds of vitaminous foodstuff, hundreds. They're all palatable. So such a nice animal, faithful, peaceful, and beneficial. After taking milk from it, if we kill, does it look very well? Even after the death, the cows supply the skin for your shoes. It is so beneficial. You see. Even after death. While living, he gives you nice milk. You cannot reject milk from the human society. As soon as there is a child born, milk immediately required. Old man, milk is life. Diseased person, milk is life. Invalid, milk is life. So therefore Kṛṣṇa is teaching by His practical demonstration how He loves this innocent animal, cow. So human society should develop brahminical culture on the basis of protecting cows. The brāhmaṇa cannot take any other food except it is made of milk preparation. That develops the finer tissues of the brain. You can understand in subtle matters, in philosophy, in spiritual science.[67]

By protecting cows and opting for milk instead of meat, he advises, civilization can become truly progressive.

One cannot become spiritually advanced without acquiring the brahminical qualifications and giving protection to cows. Cow protection ensures sufficient food prepared with milk, which is needed for an advanced civilization. One should not pollute civilization by eating the flesh of cows. A civilization must do something progressive... Instead of killing the cow to eat flesh, civilized men must prepare various milk products that will enhance the condition of society. If one follows the brahminical culture, he will become competent in Kṛṣṇa consciousness.[68]

Ingredient for yajñas

In addition to the role of milk as foodstuff, Śrīla Prabhupāda specifies cow products as necessary ingredients for religious sacrifices performed for the satisfaction of the Lord (yajñas). He stresses that yajña is required for the material as well as the spiritual benefit of society. Cow protection, he argues, supports the production of milk and other vital substances, which in turn support the total quality of life through the performance of yajñas.

Butter, when clarified by melting, produces ghee, or clarified butter, which is inevitably necessary for performing great ritualistic sacrifices. As stated in Bhagavad-gītā (18.5), yajña-dāna-tapaḥ-karma na tyājyaṁ kāryam eva tat: sacrifice, charity and austerity are essential to keep human society perfect in peace and prosperity. Yajña, the performance of sacrifice, is essential; to perform yajña, clarified butter is absolutely necessary; and to get clarified butter, milk is necessary. Milk is produced when there are sufficient cows. Therefore in Bhagavad-gītā (18.44), cow protection is recommended (kṛṣi-go-rakṣya-vāṇijyaṁ vaiśya-karma svabhāva jam).[69]

In human life, one should be trained to perform yajñas. As we are informed in Bhagavad-gītā (3.9), yajñārthāt karmaṇo 'nyatra loko 'yaṁ karma-bandhanaḥ: if we do not perform yajña, we shall simply work very hard for sense gratification like dogs and hogs. This is not civilization. A human being should be trained to perform yajña. Yajñād bhavati parjanyaḥ (BG 3.14). If yajñas are regularly performed, there will be proper rain from the sky, and when there is regular rainfall, the land will be fertile and suitable for producing all the necessities of life. Yajña, therefore, is essential. For performing yajña, clarified butter is essential, and for clarified butter, cow protection is essential. Therefore, if we neglect the Vedic way of civilization, we shall certainly suffer.[70]

Pañca-gavya, the five products received from the cow, namely milk, yogurt, ghee, cow dung and cow urine, are required in all ritualistic ceremonies performed according to the Vedic directions. Cow urine and cow dung are uncontaminated, and since even the urine and dung of a cow are important, we can just imagine how important this animal is for human civilization. Therefore the Supreme Personality of Godhead, Kṛṣṇa, directly advocates go-rakṣya, the protection of cows. Civilized men who follow the system of varṇāśrama, especially those of the vaiśya class, who engage in agriculture and trade, must give protection to the cows. Unfortunately, because people in Kali-yuga are mandāḥ, all bad, and sumanda-matayaḥ, misled by false conceptions of life, they are killing cows in the thousands. Therefore they are unfortunate in spiritual consciousness, and nature disturbs them in so many ways, especially through incurable diseases like cancer and through frequent wars and among nations. As long as human society continues to allow cows to be regularly killed in slaughterhouses, there cannot be any question of peace and prosperity.[71]

Duty of the vaiśyas (mercantile class)

Śrīla Prabhupāda teaches that, in the Vedic division of society, the mercantile and agricultural sector - known as the vaiśya class - bears responsibility toward the animals of the community, particularly the cows. Bhagavad-gītā (18.44) prescribes cow protection as one of the duties of the vaiśya class. Śrīla Prabhupāda comments:

Kṛṣi-go-rakṣya-vāṇijyaṁ vaiśya-karma svabhāva-jam (BG 18.44). Vaiśya, they should engage themselves in agricultural production and giving protection to the cows, especially mentioned, go-rakṣya. Go-rakṣya, cow protection, is one of the items of state affairs.[72]

In the Bhagavad-gītā you will find that the mercantile class... Who are mercantile class? Kṛṣi-go-rakṣya-vāṇijyaṁ vaiśya-karma svabhāva-jam (18.44). Vaiśya means the mercantile community. They are meant for giving protection to the animals, and produce grain, and distribute and make trade on them. That's all. Because formerly there was no industry—people generally depended on agricultural work—therefore the mercantile community, they used to produce food grains and distribute them, and protection of cow was their duty. As the king was entrusted to protect the life of the citizens, similarly, the vaiśya class, or the mercantile class, they were entrusted to protect the life of cow. Why particularly cow is protected? Because milk is very essential food for the human society, therefore cow protection is the duty of the human society. That is the conception of Vedic literature.[73]

There are so many facilities afforded by cow protection, but people have forgotten these arts. The importance of protecting cows is therefore stressed by Kṛṣṇa in Bhagavad-gītā (kṛṣi-go-rakṣya-vāṇijyaṁ vaiśya-karma svabhāvajam (18.44)). Even now in the Indian villages surrounding Vṛndāvana, the villagers live happily simply by giving protection to the cow. They keep cow dung very carefully and dry it to use as fuel. They keep a sufficient stock of grains, and because of giving protection to the cows, they have sufficient milk and milk products to solve all economic problems. Simply by giving protection to the cow, the villagers live so peacefully. Even the urine and stool of cows have medicinal value.[74]

Śrīla Prabhupāda highlights cow protection as an integral part of an equitable economy which promotes the well-being of all its members. Contrasting Vedic society to modern industrial society, he condemns the mass killing of cows and other animals as a practice which leads not to a higher standard of civilization but rather to degradation and suffering.

The vaiśyas, the members of the mercantile communities, are especially advised to protect the cows. Cow protection means increasing the milk productions, namely curd and butter. Agriculture and distribution of the foodstuff are the primary duties of the mercantile community backed by education in Vedic knowledge and trained to give in charity. As the kṣatriyas were given charge of the protection of the citizens, vaiśyas were given the charge of the protection of animals. Animals are never meant to be killed. Killing of animals is a symptom of barbarian society. For a human being, agricultural produce, fruits and milk are sufficient and compatible foodstuffs. The human society should give more attention to animal protection. The productive energy of the laborer is misused when he is occupied by industrial enterprises. Industry of various types cannot produce the essential needs of man, namely rice, wheat, grains, milk, fruits and vegetables. The production of machines and machine tools increases the artificial living fashion of a class of vested interests and keeps thousands of men in starvation and unrest. This should not be the standard of civilization.[75]

Special status of the cow

Although the Vedas give some allowance for animal slaughter and meat-eating under certain conditions, it is enjoined that the cow is never to be harmed. Śrīla Prabhupāda comments that although the law of subsistence mentions four-legged animals as one class of human eatable, the cow is excluded, as evident in the statement of Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam 6.4.9. He writes in his purport:

By nature's law, or the arrangement of the Supreme Personality of Godhead, one kind of living entity is eatable by other living entities. As mentioned herein, dvi-padāṁ ca catuṣ-padaḥ: the four-legged animals (catuṣ-padaḥ), as well as food grains, are eatables for human beings (dvi-padām). These four-legged animals are those such as deer and goats, not cows, which are meant to be protected. Generally the men of the higher classes of society—the brāhmaṇas, kṣatriyas and vaiśyas—do not eat meat. Sometimes kṣatriyas go to the forest to kill animals like deer because they have to learn the art of killing, and sometimes they eat the animals also. Śūdras, too, eat animals such as goats. Cows, however, are never meant to be killed or eaten by human beings. In every śāstra, cow killing is vehemently condemned... Those who desire to eat meat may satisfy the demands of their tongues by eating lower animals, but they should never kill cows, who are actually accepted as the mothers of human society because they supply milk. The śāstra especially recommends, kṛṣi-go-rakṣya: the vaiśya section of humanity should arrange for the food of the entire society through agricultural activities and should give full protection to the cows, which are the most useful animals because they supply milk to human society.[76]

Śrīla Prabhupāda argues that the cow is so important to humanity that even out of morality and simple gratitude, human society should see to it that the cow not be subject to slaughter.

Why cow protection is so much advocated? Because it is very, very important. There is no such injunction that "You don't eat the flesh of the tiger." You can eat. Because those who are meat eaters, those who are meat eaters, they have been recommended to eat the flesh of goats or other lower animals—sometimes dogs also, they eat, or the hogs—you can eat. But never the flesh of cows. So, innocent animal, the most important animal, giving service even after death... While living, giving service, so important service, giving you milk, even after death she is giving service by supplying the skin, the hoof, the horn. You utilize in so many ways. But still, the present human society is so ungrateful and rascal that they are killing cows.[77]

Śrīla Prabhupāda advises that those who insist on eating meat may follow scriptural recommendations for sacrifice and consume other animals - but never the cow. As he instructs, "First of all, they should not be meat-eater. But if you are staunch meat-eaters, then you cannot touch cow."[78]

In the matter of protecting the cows, the meat-eaters will protest, but in answer to them we may say that since Kṛṣṇa gives stress to cow protection, those who are inclined to eat meat may eat the flesh of unimportant animals like hogs, dogs, goats and sheep, but they should not touch the life of the cows, for this is destructive to the spiritual advancement of human society.[79]

Best overall benefit for humanity

Śrīla Prabhupāda writes of how cow protection bolsters the morale as well as the economic condition of the human community.

The bull is the emblem of the moral principle, and the cow is the representative of the earth. When the bull and the cow are in a joyful mood, it is to be understood that the people of the world are also in a joyful mood. The reason is that the bull helps production of grains in the agricultural field, and the cow delivers milk, the miracle of aggregate food values. The human society, therefore, maintains these two important animals very carefully so that they can wander everywhere in cheerfulness.[80]

Milking the cow means drawing the principles of religion in a liquid form... Foolish people do not know how one earns happiness by making the cows and bulls happy, but it is a fact by the law of nature. Let us take it from the authority of Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam and adopt the principles for the total happiness of humanity.[81]

The bull and the cow can be protected for the good of all human society simply by the spreading of brahminical culture as the topmost perfection of all cultural affairs. By advancement of such culture, the morale of society is properly maintained, and so peace and prosperity are also attained without extraneous effort.[82]

In summary, Śrīla Prabhupāda calls for all societies to follow the instruction of the Vedas and establish the practice of cow protection (go-rakṣya) for the best overall benefit of the human race.

The Supreme Personality of Godhead, in His instructions of Bhagavad-gītā, advises go-rakṣya, which means cow protection. The cow should be protected, milk should be drawn from the cows, and this milk should be prepared in various ways. One should take ample milk, and thus one can prolong one's life, develop his brain, execute devotional service, and ultimately attain the favor of the Supreme Personality of Godhead.[83]

(Go to references for "Cow protection and human civilization")

Civilized community

According to Vedic culture, Śrīla Prabhupāda says, animals are considered part of the community citizenry. He teaches that truly civilized society recognizes all living beings as brothers under God and affords protection for human and non-human inhabitants alike.

Mercy toward animals

Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam (7.14.9) contains this statement defining the correct attitude of humans toward animals in the community:

- mṛgoṣṭra-khara-markākhu-

- sarīsṛp khaga-makṣikāḥ

- ātmanaḥ putravat paśyet

- tair eṣām antaraṁ kiyat

- "One should treat animals such as deer, camels, asses, monkeys, mice, snakes, birds and flies exactly like one's own son. How little difference there actually is between children and these innocent animals."[84]

In his purport to this verse, Śrīla Prabhupāda comments on the Bhāgavatam's recommendation and the spiritual truths underlying it.

One who is in Kṛṣṇa consciousness understands that there is no difference between the animals and the innocent children in one's home. Even in ordinary life, it is our practical experience that a household dog or cat is regarded on the same level as one's children, without any envy. Like children, the unintelligent animals are also sons of the Supreme Personality of Godhead, and therefore a Kṛṣṇa conscious person, even though a householder, should not discriminate between children and poor animals. Unfortunately, modern society has devised many means for killing animals in different forms of life. For example, in the agricultural fields there may be many mice, flies and other creatures that disturb production, and sometimes they are killed by pesticides. In this verse, however, such killing is forbidden. Every living entity should be nourished by the food given by the Supreme Personality of Godhead. Human society should not consider itself the only enjoyer of all the properties of God; rather, men should understand that all the other animals also have a claim to God's property.[85]

As animals are inferior to humans in terms of awareness and intelligence, our mode of behavior toward animals should be one of mercy, or dayā. Śrīla Prabhupāda briefly defines dayā in this connection:

Dayā means mercy. What is dayā? Who is, I mean to say, less strong. Just like animals, birds, beast, you should be very merciful. Just like children: you should be very merciful to children. [86]

He summarizes the scriptural statements with these practical guidelines for householders (gṛhasthas):

A gṛhastha should be very much affectionate toward lower animals, birds and bees, treating them exactly like his own children. A gṛhastha should not indulge in killing animals or birds for sense gratification. He should provide the necessities of life even to the dogs and the lowest creatures and should not exploit others for sense gratification. Factually, according to the instructions of Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam, every gṛhastha is a great communist who provides the means of living for everyone. Whatever a gṛhastha may possess he should equally distribute to all living entities, without discrimination. The best process is to distribute prasāda.[87]

Śrīla Prabhupāda notes that the Vedic teachings should not be taken foolishly. Ideally, one should see with equal vision - sama-darśinaḥ - recognizing the presence of the soul and God (as the Supersoul) in every living being.[88] However, one should understand how God is present and also act appropriately in terms of material condition. In the following excerpt Śrīla Prabhupāda gives his disciples a view of the difference between wisely and foolishly 'seeing God' in the animal:

When you see a cat, when you see a dog, you see Kṛṣṇa in him. Why? You know that here is cat, living being. He, by his deeds, past deed he has got this body cat, forgetfulness. So let me help this cat, give it some Kṛṣṇa prasāda so that in some day he will come to Kṛṣṇa consciousness. This is to see in him Kṛṣṇa. Not that, "Oh, here is Kṛṣṇa, let me embrace this cat." This is nonsense. Here is a tiger, "Oh, here is Kṛṣṇa, come on. Please eat me." This is rascaldom. You should take sympathy with every living being, that he is part and parcel of Kṛṣṇa.[89]

In general, Śrīla Prabhupāda instructs that animals be seen as members of the individual family and the larger community and offered appropriate protection without discrimination.

Horses, elephants. They are also within the membership. According to Vedic conception, the animals, they are also members of your family. Because they are giving service. Not that one section of the members of my family I give protection, and the other section, I take everything from them and then cut throat. This is not civilization... Either family-wise or state-wise, it does not mean that you give protection to some members and cut throat of the others. [90]

Animals as prajāḥ (citizens)

Regarding the status of animals in human society, Śrīla Prabhupāda emphasizes the Sanskrit term prajāḥ:

Prajā means the living being who has taken his birth in the material world. Actually the living being has no birth and no death, but because of his separation from the service of the Lord and due to his desire to lord it over material nature, he is offered a suitable body to satisfy his material desires. In doing so, one becomes conditioned by the laws of material nature, and the material body is changed in terms of his own work. The living entity thus transmigrates from one body to another in 8,400,000 species of life. But due to his being the part and parcel of the Lord, he not only is maintained with all necessaries of life by the Lord, but also is protected by the Lord and His representatives, the saintly kings. These saintly kings give protection to all the prajās, or living beings, to live and to fulfill their terms of imprisonment. Mahārāja Parīkṣit was actually an ideal saintly king because while touring his kingdom he happened to see that a poor cow was about to be killed by the personified Kali, whom he at once took to task as a murderer. This means that even the animals were given protection by the saintly administrators, not from any sentimental point of view, but because those who have taken their birth in the material world have the right to live.[91]

As Śrīla Prabhupāda indicates, the meaning of prajā carries with it implications for government and community leadership. The administrative segment of society is known in the Vedas as the kṣatriya class, and the duty of the kṣatriyas is to provide protection for citizenry.[92] Śrīla Prabhupāda stresses that the kṣatriyas are meant to give protection to all who are under their dominion: "It is the duty of the kṣatriya to protect every living entity born in the land, in his kingdom. It is not that, as it is going on now, that only the human beings should be protected and not the animals."[93] Elsewhere he comments:

Vedic civilization is very liberal. According to Vedic civilization, the king has to give protection to all the prajās. Prajā means one who has taken birth in his kingdom. Prajāyate. So the animal is also prajā of the government. The trees are also prajā of the government. So formerly nobody could slaughter an animal, nobody can cut even a tree without reason, without sanction by the Vedic injunction.[94]

A kṣatriya must be vīra, hero. Whenever there is injustice, he must immediately come forward. "Why injustice? These poor animals, they are also my subject. How you can kill them? He's also born in this land." "National" means one is born in that particular land. So they are also born in this land. Why he should be treated differently? Just like in your country, even one Indian gets his child here, the child is counted as USA-born, US citizen, eh? Immediately. So if that is the law, that anyone born in this land should be treated as national, what is this law that the cows and the bulls born in that land, they are to be slaughtered?[95]

Śrīla Prabhupāda notes that in the absence of kṣatriya principles of community protection, government policy adversely affects more than just the animals of society.

Exact good government law means that anyone who kills an animal without sanction... Of course, they now give sanction, that "Yes, you can kill as many animals in the slaughterhouse as you like." Because the government is śūdra. Government is not kṣatriya. So therefore is no protection. Why animal? Even a human being, if he's being killed on the street, on the Broadway, nobody cares for him. So this is the position.[96]

Brotherhood of all

Śrīla Prabhupāda teaches that civilized society is one in which all living beings are recognized as children of God. Witnessing events of his own time, he saw that civilization’s ideals of humanity and brotherhood would remain flawed unless the leaders of human society came to this understanding.

The so-called nationalist or humanitarist or universalist, they are packed up within the boundary of the human being. They have no expansions toward other living entities. Their national conception, that the human body should be given protection but animal body no protection... Why? They are also nationals. But they have no such idea because all these ideas are defective. There is shortcut.[97]

In one conversation with his disciples, Śrīla Prabhupāda voiced his stand against the 'humanitarian' attitude of the day:

You are trying to unify the so-called human beings, but you are keeping the poor animals for cutting their throat. This is your humanity. Because these poor animals cannot protest, so you are strong. And this is your humanity, you cut their throat and eat. But that is not humanity. Humanity is here mentioned: God is the seed-giving father all living entities. That is the fact. That is humanity. They do not know what is meaning by humanity. Here is the explanation, humanity. That is called brahma-bhūtaḥ prasannātmā (BG 18.54). Unless you come to that stage, there is no question of humanity. Artificially, you manufacture something and you think humanity. According to your convenience. "Let us combine together and exploit other living entities for our benefit." That is not humanity. They do not know what is humanity. Here is the explanation. How humanity can be established unless there is the understanding of the supreme father, how there is question of, how this question of brotherhood can come in?[98]

In another discussion, he commented on the knowledge gap involved in common humanitarian activities:

The same man, he is giving charity for feeding poor man or giving relief to the distressed man, but at the same time he's encouraging animal-killing. So what is the ethics? What is the ethical law in these two contradictory activities? One side... Just like our Vivekananda. He is advocating daridra-nārāyaṇa sevā, "Feed the poor," but feed the poor with mother Kālī's prasāda, where poor goats are killed. Just like, another, one side feeding the poor, another side killing the poor goat. So what is the ethic? What is the ethical law in this connection? Just like people open hospitals, and the doctor prescribes, "Give this man," what it is called, "(Hindi), ox blood, or chicken juice." So what is this ethic? And they're supporting that "Here is chicken juice." Just because animal has no soul, so they can be killed. This is another theory. So why the animal has no soul? So imperfect knowledge. So on the basis of imperfect knowledge this ethic or this humanitarian, what is the value?[99]

Śrīla Prabhupāda defines the ideal of civilized society in this description of Āryan civilization given in his purport to Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam 6.16.43:

The members of human society who strictly follow the principles of bhāgavata-dharma and live according to the instructions of the Supreme Personality of Godhead are called Āryans or ārya. A civilization of Āryans who strictly follow the instructions of the Lord and never deviate from those instructions is perfect. Such civilized men do not discriminate between trees, animals, human beings and other living entities. Paṇḍitāḥ sama-darśinaḥ: (BG 5.18) because they are completely educated in Kṛṣṇa consciousness, they see all living beings equally. Āryans do not kill even a small plant unnecessarily, not to speak of cutting trees for sense gratification. At the present moment, throughout the world, killing is prominent. Men are killing trees, they are killing animals, and they are killing other human beings also, all for sense gratification. This is not an Āryan civilization. As stated here, sthira-cara-sattva-kadambeṣv apṛthag-dhiyaḥ. The word apṛthag-dhiyaḥ indicates that Āryans do not distinguish between lower and higher grades of life. All life should be protected. All living beings have a right to live, even the trees and plants. This is the basic principle of an Āryan civilization.[100]

(Go to references for "Civilized community")

Non-theistic perspectives

While Śrīla Prabhupāda's presentation is primarily theistic, he also advances arguments without specific reference to God to oppose the practice of animal-killing. This section highlights three angles of reasoning: natural design (human physiology and resources for food), common morality (observable without reference to God), and economics (focusing on material prosperity and utilization of material resources).

Natural design

Śrīla Prabhupāda teaches that flesh-eating for humans is neither necessary nor truly natural. There is no need to kill animals, he says, as one can stay healthy eating a variety of foods without resorting to bloodshed.

Milk, butter, cheese and similar products give animal fat in a form which rules out any need for the killing of innocent creatures. It is only through brute mentality that this killing goes on. The civilized method of obtaining needed fat is by milk. Slaughter is the way of subhumans. Protein is amply available through split peas, dāl, whole wheat, etc.[101]

He advocates utilizing milk instead of meat for comparable nutrition without violence.

Milk - accepting that cow flesh and blood is very nutritious, that we also admit - but a civilized man utilizes the blood and meat in a different way. The milk is nothing but blood. But it is transformed into milk. And again, from milk you make so many things. You make yogurt, you make curd, you make ghee, so many things. And combination of these milk products with grains, with fruits and vegetables, you make similar hundreds of preparation. So this is civilized life, not that directly kill one animal and eat... Why you should kill?[102]