ES/Discusion filosofica sobre Ludwig Wittgenstein (Syamasundara)

******Documento pendiente de editar******

Śyāmasundara: This morning we are discussing a philosopher called Ludwig Wittgenstein, a contemporary German philosopher. One of his major so-called contributions is what is called a verification principle, which reads, “To understand a proposition means to know what is the case if it is true”. That means anyone who wishes to understand a proposition must first know the conditions under which that proposition is true, that is, what information is required by way of evidence of its truth. Śyāmasundara: Esta mañana estamos hablando de un filósofo llamado Ludwig Wittgenstein, un filósofo alemán contemporáneo. Una de sus principales contribuciones es lo que se llama principio de verificación, que dice: “Entender una proposición significa saber cuál es el caso si es verdadera”. Eso significa que cualquiera que desee entender una proposición debe conocer primero las condiciones bajo las cuales esa proposición es verdadera, es decir, qué información se requiere a modo de prueba de su verdad.

Prabhupāda: So the modern world's proposition is that “I am this body”. So that is untruth. What does he say about this? Prabhupāda: Así que la propuesta del mundo moderno es que “yo soy este cuerpo”. Así que eso es una falsedad. ¿Qué dice sobre esto?

Śyāmasundara: Well, if I claim that I am this body, that means I have to know all of the conditions which make it true that I am this body. Then if all these conditions are true... Śyāmasundara: Bueno, si afirmo que soy este cuerpo, eso significa que tengo que conocer todas las condiciones que hacen que sea cierto que soy este cuerpo. Entonces, si todas estas condiciones son verdaderas...

Prabhupāda: First of all we must discuss what I am. Then we have to see whether I am this body or not. And what do you mean by “I am”? You are individual, I am individual. How I exact my individuality, and how you exact your individuality? What is the symptom? What is the meaning of “I am”? First of all you have to understand, what do you mean by “I am”? “I am” means my activities, “I am”. That is “I am”. Prabhupāda: En primer lugar, debemos discutir lo que soy. Luego tenemos que ver si soy este cuerpo o no. Y ¿qué quieres decir con “yo soy”? Usted es individual, yo soy individual. ¿Cómo preciso mi individualidad y cómo precisas tú tu individualidad? ¿Cuál es el síntoma? ¿Cuál es el significado de “yo soy”? En primer lugar, tienes que entender, ¿qué quieres decir con “yo soy”? “Yo soy” significa mis actividades, “Yo soy”. Eso es “yo soy”.

Śyāmasundara: My activities. Śyāmasundara: Mis actividades.

Prabhupāda: Yes. So try to understand, “I am” means my activities. So how my activities are going on? Presently we can see my activities are going on by the movements of my senses, of the limbs of the body. Therefore we come to the point that the moving force is “I am”. Prabhupāda: Sí. Así que trata de entender que “yo soy” significa mis actividades. Entonces, ¿cómo se desarrollan mis actividades? Actualmente podemos ver que mis actividades se desarrollan por los movimientos de mis sentidos, de los miembros del cuerpo. Por lo tanto, llegamos al punto de que la fuerza en movimiento es “yo soy”.

Śyāmasundara: That which moves the limbs. Śyāmasundara: Lo que mueve los miembros.

Prabhupāda: Yes. That moving force, if “I am,” then I am not this body, because as soon as the moving force from the body is gone, the body is of no value. Prabhupāda: Sí. Esa fuerza móvil, si “yo soy”, entonces no soy este cuerpo, porque tan pronto como la fuerza móvil del cuerpo desaparece, el cuerpo no tiene valor.

Śyāmasundara: They would say that then “I” cease to exist. Then “I am” no more. When the body dies, then I am no more. Śyāmasundara: Dirían que entonces “yo” dejo de existir. Entonces “yo” ya no soy. Cuando el cuerpo muere, entonces ya no soy.

Prabhupāda: Then how do you come to “I am”? “No more” means you came to the existence of “I am”. How did you come to exist as “I am”? If you say that after the stoppage of movements of the body, when there is no more “I am,” then how this “I am” came into existence? That is the question. Wherefrom this movement came? Prabhupāda: ¿Entonces cómo llegas al “yo soy”? “No más” significa que llegaste a la existencia de “yo soy”. ¿Cómo llegaste a la existencia de “yo soy”? Si usted dice que después de la detención de los movimientos del cuerpo, cuando ya no hay “yo soy”, entonces ¿cómo llegó a existir este “yo soy”? Esa es la pregunta. ¿De dónde vino este movimiento?

Śyāmasundara: They say that the condition or the evidence required to know if this is true, that I came from... Śyāmasundara: Dicen que la condición o la evidencia requerida para saber si esto es cierto, que yo vine de...

Prabhupāda: The first thing is that if I identify myself with the body, the body means movements of the limbs. Now if something is wanting, and the limbs do not move any more... But that moving force is “I am”. Prabhupāda: Lo primero es que si me identifico con el cuerpo, el cuerpo significa movimientos de los miembros. Ahora bien, si algo falta y los miembros ya no se mueven... Pero esa fuerza de movimiento es “yo soy”.

Śyāmasundara: They would say that it is a combination of chemicals or some... Śyāmasundara: Dirían que es una combinación de productos químicos o algún...

Devānanda: They postulated... The French philosophers at one point postulated that within the matter itself there is a potential of consciousness. They called it elan vital, living potential within matter, and when you put the matter together in certain positions, then that living potential is able to come out, and when the material nature changes again, it is no longer manifested. Devānanda: Postularon... Los filósofos franceses en un momento dado postularon que dentro de la materia misma hay un potencial de conciencia. Lo llamaron elan vital, potencial viviente dentro de la materia y cuando pones la materia en ciertas posiciones, entonces ese potencial viviente es capaz de salir y cuando la naturaleza material cambia de nuevo, ya no se manifiesta.

Prabhupāda: That is another nonsense, because when the body becomes from the lump of matter, why that living potentiality, consciousness, does not come again? Prabhupāda: Esa es otra tontería, porque cuando el cuerpo se convierte de la masa de materia, ¿por qué esa potencialidad viviente, la conciencia, no viene de nuevo?

Devānanda: Because the elements are no longer in suitable arrangement for life to be... Devānanda: Porque los elementos ya no están en la disposición adecuada para que haya vida...

Prabhupāda: If you know the elements, you say that “You add this element”. Just like when the motorcar stops for want of gas, you take gasoline from the petroleum store and it starts again. Either you do it, otherwise you are rascal, you are putting some wrong theory. If you say that it is a combination of chemicals, and you know that addition, that these living symptoms are there, then bring that chemical and add to it and let the body go out again. If you cannot do that, then you are nonsense. There is no sense of your statement. Prabhupāda: Si usted conoce los elementos, dice que “añade este elemento”. Al igual que cuando el automóvil se detiene por falta de gasolina, usted toma gasolina de la tienda de petróleo y vuelve a arrancar. O lo haces, de lo contrario eres un bribón, estás poniendo una teoría equivocada. Si dices que es una combinación de químicos y sabes que la adición, que estos síntomas vivos están ahí, entonces trae ese químico y agrégalo y deja que el cuerpo salga de nuevo. Si no puedes hacer eso, entonces no tienes sentido. Tu afirmación no tiene sentido.

Devānanda: So in other words, if a body dies from heart failure, they should immediately be able to remove that heart and put in a fresh heart from somebody who has just died, and it will come back to life. But it doesn't do that. Devānanda: En otras palabras, si un cuerpo muere por un fallo cardíaco, deberían poder extraer inmediatamente ese corazón y poner un corazón nuevo de alguien que acaba de morir y volverá a la vida. Pero no se hace eso.

Prabhupāda: No. There are so many other things, and not only one case of heart failure. Prabhupāda: No. Hay muchas otras cosas, y no sólo un caso de insuficiencia cardíaca.

Devānanda: But there are many, for example... Devānanda: Pero hay muchos, por ejemplo...

Prabhupāda: Don't you...

Śyāmasundara: We want to stick to Wittgenstein. Śyāmasundara: Queremos seguir con Wittgenstein.

Prabhupāda: The main principle is when the body is called dead, why don't you put some chemicals and make it alive again? You say something is wanted. What is that something? That you do not know. But we can say what is that something. We say that something is the soul. That is wanting. Prabhupāda: El principio fundamental es que cuando se dice que el cuerpo está muerto, ¿por qué no se ponen algunos productos químicos y se le hace revivir? Usted dice que se quiere algo. ¿Qué es ese algo? Eso no se sabe. Pero podemos decir qué es ese algo. Decimos que ese algo es el alma. Eso es lo que se quiere.

Śyāmasundara: So far that proposition, you said “I am” means that the soul exists. That is your proposition. Śyāmasundara: Hasta ahora esa proposición, usted dijo “yo soy” significa que el alma existe. Esa es su proposición.

Prabhupāda: My proposition is that “I am” means I am the soul, spirit soul, not this body. Prabhupāda: Mi propuesta es que “yo soy” significa que soy el alma, el alma espiritual, no este cuerpo.

Śyāmasundara: So they say that if we are to verify this proposition, to prove that it is true, then we have to know what conditions under which it is true. What are those conditions under which it is true? Śyāmasundara: Así que dicen que si vamos a verificar esta proposición, para demostrar que es verdadera, entonces tenemos que saber bajo qué condiciones es verdadera. ¿Cuáles son esas condiciones bajo las que es verdadera?

Prabhupāda: It is very simple. So long the soul is there, it is moving, and as soon as the soul is out, it is not moving. Anyone can understand. You say something is wanting. I say it is soul, definitely. But you do not know what is that something. Therefore your knowledge is imperfect, my knowledge is perfect. My knowledge is supported by Bhagavad-gītā, but your knowledge has no support; therefore your knowledge is nonsense. Prabhupāda: Es muy sencillo. Mientras el alma está ahí, se mueve y tan pronto como el alma está fuera, no se mueve. Cualquiera puede entenderlo. Tú dices que hay algo que falta. Yo digo que es el alma, definitivamente. Pero tú no sabes qué es ese algo. Por lo tanto, tu conocimiento es imperfecto, mi conocimiento es perfecto. Mi conocimiento se apoya en el Bhagavad-gītā, pero tu conocimiento no tiene apoyo; por tanto, tu conocimiento no tiene sentido.

Śyāmasundara: In order for that statement or that proposition to be true, there must be evidence. Śyāmasundara: Para que esa declaración o esa proposición sea verdadera, debe haber evidencia.

Prabhupāda: This is evidence: that there is no soul. The self, the individual soul, is now departed; therefore this body is lump of matter. This is evidence. And because the soul is there, therefore the body changes or develops. Just like if a child is born dead, then the body does not develop or changes. It remains in the same condition. But so long the soul is there, the child grows or changes his body. That is evidence. Because the soul is there, therefore the child is growing or changing body from childhood to boyhood, boyhood to youth. Suppose a child is born, doctor says it is dead child. You say something is wanted, but what is that something? You do not know. Otherwise, if you know, you add it. What is that something? Suggest, what is that something? Simply vague idea something, that is nonsense idea. That is not science. You must give, “This is wanting”. Suppose that you say that the blood, the redness, just like nowadays blood supply is the theory, so what is this blood? Blood is a liquid, red liquid, like chemical or something, with some salt. So you can add salt, just like in cholera cases, they add saline injection. So dead body, you give saline injection, make it red by some color, give him life. If you say that “Red blood is now white,” so make it red. What is the difficulty? There is no difficulty. There are so many chemicals. If you say the redness is the life, then there are many natural products, just like jewels, by nature it is red. Why is it not alive? Why it is not alive? By natural redness of something, if you say that is the cause of life, then there are many jewels. What is called, jewels? Prabhupāda: Esta es la evidencia: que no hay alma. El yo, el alma individual, ya ha partido; por lo tanto, este cuerpo es un trozo de materia. Esto es una evidencia. Y debido a que el alma está allí, por lo tanto, el cuerpo cambia o se desarrolla. Al igual que si un niño nace muerto, entonces el cuerpo no se desarrolla o cambia. Permanece en la misma condición. Pero mientras el alma esté ahí, el niño crece o cambia su cuerpo. Eso es una evidencia. Debido a que el alma está allí, por lo tanto, el niño está creciendo o cambiando su cuerpo de la infancia a la niñez, de la niñez a la juventud. Supongamos que un niño nace, el médico dice que es un niño muerto. Usted dice que se necesita algo, pero ¿qué es ese algo? No lo sabes. De lo contrario, si lo sabes, lo añades. ¿Qué es ese algo? Sugiere, ¿qué es ese algo? Simplemente una vaga idea de algo, eso es una idea sin sentido. Eso no es ciencia. Debes decir: “Esto es lo que falta”. Supongamos que usted dice que la sangre, el enrojecimiento, al igual que hoy en día el suministro de sangre es la teoría, así que ¿qué es esta sangre? La sangre es un líquido, un líquido rojo, como un producto químico o algo así, con algo de sal. Así que se puede añadir sal, al igual que en los casos de cólera, se añade una inyección de solución salina. Así que, a un cuerpo muerto, le das una inyección de sal, lo haces rojo por algún color, le das vida. Si dices que “la sangre roja es ahora blanca”, entonces hazla roja. ¿Cuál es la dificultad? No hay ninguna dificultad. Hay muchos productos químicos. Si dices que el rojo es la vida, entonces hay muchos productos naturales, como las joyas, por naturaleza es rojo. ¿Por qué no está vivo? ¿Por qué no está vivo? Si dices que el rojo natural de algo es la causa de la vida, entonces hay muchas joyas. ¿Cómo se llaman las joyas?

Śyāmasundara: Rubí.

Prabhupāda: Ruby. Why it is not alive? Redness is there. Therefore we have to accept your identification with the soul, not with this body; otherwise this is nonsense. Prabhupāda: Rubí. ¿Por qué no está vivo? La rojez está ahí. Por lo tanto, tenemos que aceptar su identificación con el alma, no con este cuerpo; de lo contrario, esto no tiene sentido.

Śyāmasundara: He is not disputing that there is soul or there is not soul. He is merely putting forward a principle to test something, if it is true or false. Śyāmasundara: Él no está discutiendo si hay alma o no hay alma. Simplemente está presentando un principio para probar algo, si es verdadero o falso.

Prabhupāda: This is the test. This is the test. Because the soul is there, therefore the body is moving. Prabhupāda: Esta es la prueba. Esta es la prueba. Porque el alma está ahí, por lo tanto, el cuerpo se mueve.

Śyāmasundara: So that is the evidence for... Śyāmasundara: Así que esa es la evidencia de...

Prabhupāda: That is the evidence. Anyone can see. Now we say, “My father is gone. Oh, my father is gone”. Where has he gone? Your father is lying there. Why do you say gone? Prabhupāda: Esa es la evidencia. Cualquiera puede verlo. Ahora decimos: “Mi padre se ha ido. Oh, mi padre se ha ido”. ¿Dónde se ha ido? Tu padre está ahí tirado. ¿Por qué dices que se ha ido?

Devānanda: They say he has passed away. But what is passed away? Devānanda: Dicen que ha fallecido. Pero, ¿qué es lo que ha fallecido?

Prabhupāda: Passed away... What is this passed away? That means you have not seen your father. You have not seen your father, still you identify the body as your father. Or your father identifies your body as yourself. Just like the father has not seen the son, the son has not seen the father. Therefore it is illusion. Prabhupāda: Fallecido... ¿Qué es eso de “fallecido”? Eso significa que no has visto a tu padre. No has visto a tu padre, pero identificas el cuerpo como tu padre. O tu padre identifica tu cuerpo como tú mismo. Al igual que el padre no ha visto al hijo, el hijo no ha visto al padre. Por lo tanto, es una ilusión.

Śyāmasundara: The movement of the body is evidence that the soul exists. Śyāmasundara: El movimiento del cuerpo es una prueba de que el alma existe.

Prabhupāda: Yes. That is the only evidence. Because the soul is there, that individual soul. Prabhupāda: Sí. Esa es la única evidencia. Porque el alma está ahí, esa alma individual.

Devānanda: Śrīla Prabhupāda, when death comes, at the moment... Before death, the whole body is alive, completely alive and functioning, and in a split second it's all finished, completely dead. That would be an evidence that it is not a chemical combination. If it were a chemical combination it would die slowly. Devānanda: Śrīla Prabhupāda, cuando llega la muerte, en el momento... Antes de la muerte, todo el cuerpo está vivo, completamente vivo y funcionando y en una fracción de segundo está todo acabado, completamente muerto. Eso sería una evidencia de que no es una combinación química. Si fuera una combinación química, moriría lentamente.

Prabhupāda: The reason is that the soul, when quitting this body, there is examination what kind of body he is going to get. Superior examination. Either you call nature or God, there is superior... According to his karma he will get a body. Now, that requires a little time. So what kind of body this soul will get? As soon as it is decided, then immediately he's transferred to that kind of body, and this body remains there. Prabhupāda: La razón es que el alma, al dejar este cuerpo, se examina qué clase de cuerpo va a recibir. Un examen superior. Ya sea que llames a la naturaleza o a Dios, hay un examen superior... De acuerdo con su karma obtendrá un cuerpo. Ahora, eso requiere un poco de tiempo. Entonces, ¿qué tipo de cuerpo obtendrá esta alma? Tan pronto como se decide, entonces inmediatamente es transferido a ese tipo de cuerpo, y este cuerpo permanece allí.

Śyāmasundara: This would also, it seems, satisfy his second requirement for verification, that sense observation or information ultimately derived by means of sense observation is necessary for verification. Śyāmasundara: Esto también satisfaría, al parecer, su segundo requisito para la verificación, que la observación de los sentidos o la información derivada en última instancia por medio de la observación de los sentidos es necesaria para la verificación.

Prabhupāda: This is sense observation. It not nonsensical; it is complete sense, sensible, that now this soul has passed and quit this body - death. So the body is not the man; the soul is the man. This is quite sensible. It is not nonsensical. Otherwise how do you explain? You explain what is that distinction between dead body and living body. What is your sensible explanation, according to this philosopher? Prabhupāda: Esto es una observación sensorial. No es un sinsentido; es completamente sensato, sensible, que ahora esta alma ha pasado y dejado este cuerpo - la muerte. Así que el cuerpo no es el hombre; el alma es el hombre. Esto es muy sensato. No es absurdo. Si no, ¿cómo lo explicas? Explica qué es esa distinción entre cuerpo muerto y cuerpo vivo. ¿Cuál es tu explicación sensata, según este filósofo?

Śyāmasundara: He isn't quibbling with that. His only philosophy was that he was putting forward ways of determining what is true and what is false. Śyāmasundara: No está discutiendo eso. Su única filosofía era que proponía formas de determinar lo que es verdadero y lo que es falso.

Prabhupāda: So that is evidence that this body is false, the soul is true. That is our statement. Body is false. Just like this, this (indistinct), this sweater, this is false. It has got a hand but it is false hand. The real hand is within, within the shirt, that is real hand. Similarly, this body also. It is compared with dress. The dress is false. The man who puts on the dress, he is true. Similarly, the soul is the truth and the body is false. If you want to make distinction between false and true, then this is the distinction: the soul is the truth, the body is false. Prabhupāda: Así que eso es una prueba de que este cuerpo es falso, el alma es verdadera. Esa es nuestra afirmación. El cuerpo es falso. Así como esto, este (inaudible), este suéter, esto es falso. Tiene una mano, pero es una mano falsa. La verdadera mano está dentro, dentro de la camisa, esa es la verdadera mano. Del mismo modo, este cuerpo también. Se compara con el vestido. El vestido es falso. El hombre que se pone el vestido, es verdadero. Del mismo modo, el alma es la verdad y el cuerpo es falso. Si quieres distinguir entre lo falso y lo verdadero, entonces esta es la distinción: el alma es la verdad, el cuerpo es falso.

Śyāmasundara: He says that philosophy is that mental activity which seeks to analyze or clarify the meanings of scientific propositions. Śyāmasundara: Dice que la filosofía es aquella actividad mental que busca analizar o aclarar los significados de las proposiciones científicas.

Prabhupāda: This is philosophy: to study what is this body and how it is moving. This is analytical study. And you come to the understanding that the body is a dead lump of matter, there is something which is called the soul. Because the soul is there. This is scientific truth. One who has not this knowledge, he is not scientific; he is foolish. Prabhupāda: Esto es filosofía: estudiar qué es este cuerpo y cómo se mueve. Esto es un estudio analítico. Y llegas a comprender que el cuerpo es un bulto muerto de materia, hay algo que se llama alma. Porque el alma está ahí. Esta es la verdad científica. Aquel que no tiene este conocimiento, no es científico; es tonto.

Śyāmasundara: In other words, if you make a scientific proposition that “Because I am, the body moves,” that is your scientific proposition? Śyāmasundara: En otras palabras, si haces una proposición científica de que “Porque yo estoy, el cuerpo se mueve”, ¿esa es tu proposición científica?

Prabhupāda: Yes, this is scientific proposition. Prabhupāda: Sí, es una propuesta científica.

Śyāmasundara: Then philosophy is a clarification of that proposition. Śyāmasundara: Entonces la filosofía es una aclaración de esa proposición.

Prabhupāda: Clarification... It is supported by the greatest authority, Kṛṣṇa. Dehino 'smin yathā dehe kaumāraṁ yauvanaṁ jarā, tathā dehāntara-prāptiḥ (BG 2.13). He says that, the greatest authority, God Himself, He says that as the body's changing in different phases of my life, similarly, ultimately, at the end, this body is left and another body is accepted. That is scientific. It is not our bogus proposition. It is supported by the whole Vedic knowledge and especially by Kṛṣṇa, and who can be greater authority than Kṛṣṇa? That will be scientific. Just like modern science: if somebody proves some theory and it is accepted by the scientific world, then it is accepted as scientific; similarly, our proposition is accepted by Kṛṣṇa, the greatest scientist; therefore it is fact. But you have no support by the scientists, what you say; therefore your proposition is nonsense. My proposition is accepted by the greatest scientist. He has created this whole world. Prabhupāda: Aclaración... Lo sostiene la mayor autoridad, Kṛṣṇa. Dehino 'smin yathā dehe kaumāraṁ yauvanaṁ jarā, tathā dehāntara-prāptiḥ (BG 2.13). Él dice que, la mayor autoridad, Dios mismo, Él dice que como el cuerpo está cambiando en diferentes fases de mi vida, de manera similar, en última instancia, al final, se deja este cuerpo y se acepta otro cuerpo. Eso es científico. No es nuestra propuesta falsa. Es apoyado por todo el conocimiento védico y especialmente por Kṛṣṇa y ¿quién puede ser mayor autoridad que Kṛṣṇa? Eso será científico. Al igual que la ciencia moderna: si alguien demuestra alguna teoría y es aceptada por el mundo científico, entonces es aceptada como científica; de manera similar, nuestra proposición es aceptada por Kṛṣṇa, el mayor científico; por lo tanto, es un hecho. Pero usted no tiene ningún apoyo de los científicos, lo que usted dice; por eso su proposición es una tontería. Mi proposición es aceptada por el más grande científico. Él ha creado todo este mundo.

Śyāmasundara: He says that philosophers present old facts in new light, but philosophers do not discover any new facts. Śyāmasundara: Dice que los filósofos presentan hechos antiguos bajo una nueva luz, pero los filósofos no descubren ningún hecho nuevo.

Prabhupāda: Because they're all rascals and fools, what they can discover? (laughter) They simply theorize on their rascaldom, that's all. That is their business. (indistinct) There is no fact. And those who are rascals, they believe them. That's all. So we are not such rascals, because our knowledge is received from the greatest scientist, Kṛṣṇa. I personally may be rascal, but because I follow the greatest scientist, therefore my proposition is scientific. I do not know how this dictaphone is working, but somebody has said “This is dictaphone,” I accept. And it is working. That is my scientific knowledge. I may not be the mechanic, but I am working. Prabhupāda: Porque son todos unos bribones y unos tontos, ¿qué pueden descubrir? (Risas) Ellos simplemente teorizan sobre su bribonería, eso es todo. Ese es su negocio (inaudible). No hay ningún hecho. Y los que son bribones, les creen. Eso es todo. Así que nosotros no somos tales bribones, porque nuestro conocimiento lo recibimos del más grande científico, Kṛṣṇa. Yo personalmente puedo ser un bribón, pero como sigo al más grande científico, por ello mi proposición es científica. No sé cómo funciona este dictáfono, pero alguien ha dicho “Esto es un dictáfono”, lo acepto. Y está funcionando. Ese es mi conocimiento científico. Puede que no sea el mecánico, pero estoy trabajando.

Śyāmasundara: He says that philosophy is a process which attempts to clarify God, not that itself it has factual content. Śyāmasundara: Dice que la filosofía es un proceso que intenta esclarecer a Dios, no que en sí misma tenga contenido fáctico.

Prabhupāda: This is clarification. Mostly the people are under illusion, identifying the body with the self. But we are clarifying that “You are not this body, you are spirit soul”. Therefore it is a scientific proposition. Prabhupāda: Esto es una aclaración. La mayoría de las personas están bajo la ilusión, identificando el cuerpo con el yo. Pero estamos aclarando que “Tú no eres este cuerpo, eres alma espiritual”. Por lo tanto, es una proposición científica.

Śyāmasundara: So we are clarifying a scientific proposition with our philosophy. Śyāmasundara: Así que estamos aclarando una proposición científica con nuestra filosofía.

Prabhupāda: Yes. This is it. Philosophy means the science of sciences. Another definition of philosophy is “the science of sciences”. All sciences are derived from philosophy. So philosophy's actual position is on the higher level than the sciences. Prabhupāda: Sí. Esto es. Filosofía significa la ciencia de las ciencias. Otra definición de filosofía es “la ciencia de las ciencias”. Todas las ciencias se derivan de la filosofía. Así que la posición real de la filosofía está en el nivel superior de las ciencias.

Śyāmasundara: Another definition he has is that “Philosophy is the pursuit of meaning”. Pursuit of meaning. Śyāmasundara: Otra definición que tiene es que “La filosofía es la búsqueda del sentido”. La búsqueda del sentido.

Prabhupāda: Yes. Because philosophy is the searching out about the ultimate truth, therefore it is pursuit; and the ultimate truth is meaning. That is nice. But there are different philosophers, and so far we are concerned, we know that the ultimate meaning is Kṛṣṇa, sarva-kāraṇa-kāraṇam (Bs. 5.1), the cause of all causes; therefore our philosophy is perfect. They are simply pursuing, but we have reached the goal. That is the difference. They are on the way, but we are on the spot. Is that right? Prabhupāda: Sí. Porque la filosofía es la búsqueda de la verdad última, por lo tanto, es una búsqueda y la verdad última es el significado. Eso es bueno. Pero hay diferentes filósofos y en lo que a nosotros respecta, sabemos que el significado último es Kṛṣṇa, sarva-kāraṇa-kāraṇam (Bs. 5.1), la causa de todas las causas; por tanto, nuestra filosofía es perfecta. Ellos simplemente persiguen, pero nosotros hemos alcanzado la meta. Esa es la diferencia. Ellos están en el camino, pero nosotros estamos en el lugar. ¿Es eso cierto?

Śyāmasundara: Yes. (laughs) He says that the propositions of logic and mathematics are tautologies, he calls it, or uninformative assertions which state nothing factual about the world. Just like, for instance, “Two plus two equals four”. On paper it is just two symbols: the symbol 2, and the symbol 2 and the symbol 4. But actually that is a void arrangement. It doesn't state anything factual about the world. FALTÓ: Śyāmasundara: Sí (risas) Dice que las proposiciones de la lógica y las matemáticas son tautologías, como él las llama, o afirmaciones no informativas que no dicen nada sobre el mundo. Como, por ejemplo, “Dos más dos es igual a cuatro”. Sobre el papel son sólo dos símbolos: el símbolo 2 y el símbolo 2 y el símbolo 4. Pero en realidad es una disposición nula. No afirma nada fáctico sobre el mundo.

Prabhupāda: What does he want more practical? Prabhupāda: ¿Qué quiere más práctico?

Śyāmasundara: He says that these can be demonstrated but not verified. Śyāmasundara: Dice que se pueden demostrar pero no verificar.

Prabhupāda: Why not verified? Two rupees plus two rupees equal to four rupees. This is verified. Prabhupāda: ¿Por qué no se verifica? Dos rupias más dos rupias equivalen a cuatro rupias. Esto está verificado.

Śyāmasundara: But that's something else. Śyāmasundara: Pero eso es otra cosa.

Prabhupāda: That is..., the mathematics is required for that purpose. You have got two rupees, I have got two rupees; when combined together it becomes four rupees. That is mathematics. This is practical proof. Why does he say that there is no practical use? And philosopher, to become philosopher is not to become a nonsense. But because he theorizes something nonsensical, he's become a philosopher - that is not philosophy. This mathematical truth is practically true. Prabhupāda: Eso es..., la matemática se requiere para ese propósito. Tú tienes dos rupias, yo tengo dos rupias; cuando se combinan se convierten en cuatro rupias. Eso es matemática. Esto es una prueba práctica. ¿Por qué dice que no hay uso práctico? Y el filósofo, convertirse en filósofo no es convertirse en una tontería. Pero porque él teoriza algo sin sentido, se ha convertido en un filósofo - eso no es filosofía. Esta verdad matemática es prácticamente cierta.

Śyāmasundara: Let us say the proposition that “The sum of the angles of a triangle equals 180 degrees,” that is a proposition. It can be demonstrated on paper but it cannot be verified by experiential data. Śyāmasundara: Digamos que la proposición “La suma de los ángulos de un triángulo es igual a 180 grados”, es una proposición. Se puede demostrar sobre el papel, pero no puede ser verificada por los datos de la experiencia.

Devotee: If you're steering a ship you can make use of it, can't you? Devoto: Si estás dirigiendo un barco puedes hacer uso de él, ¿no?

Śyāmasundara: It can be made use of and it can be called valid or invalid. Śyāmasundara: Se puede hacer uso y se puede llamar válido o inválido.

Prabhupāda: What does he want more? Prabhupāda: ¿Qué más quiere?

Śyāmasundara: He wants to know true and false. That this “Sum of the angles equal to 180 degrees” can be said to be valid or invalid, but it cannot be said to be true or false. Śyāmasundara: Quiere saber lo verdadero y lo falso. Que esta “Suma de los ángulos igual a 180 grados” se puede decir que es válida o inválida, pero no se puede decir que sea verdadera o falsa.

Prabhupāda: Then in that way, what he proposes, that is also false, because in this material world there is no truth. Everything is false. So his philosophical proposition is also false. Prabhupāda: Entonces, de ese modo, lo que él propone, eso también es falso, porque en este mundo material no hay verdad. Todo es falso. Así que su propuesta filosófica también es falsa.

Śyāmasundara: Actually, he came to recognize that. Śyāmasundara: En realidad, llegó a reconocerlo.

Prabhupāda: Yes. Then that's all right. Then why he is bothering about something false? That is another foolishness. “Prabhupāda”: Sí. Entonces está bien. Entonces, ¿por qué se preocupa por algo falso? Esa es otra tontería.

Devānanda: I thought that that was a Māyāvādī theory, that everything is false. Devānanda: Yo pensaba que esa era una teoría Māyāvādī, que todo es falso.

Prabhupāda: Yes. He wants to accept false, again make botheration. Prabhupāda: Sí. Quiere aceptar lo falso, volver a hacer la molestia.

Śyāmasundara: No. He does not say false, he says that the sum of the... Śyāmasundara: No. Él no dice falso, dice que la suma de los...

Prabhupāda: Better thing is that as we say, it is not false, but it is temporary. Prabhupāda: Lo mejor es que como decimos, no es falso, pero es temporal.

Śyāmasundara: He doesn't say true or false, he says that the sum of the angles... Śyāmasundara: No dice verdadero o falso, dice que la suma de los ángulos...

Prabhupāda: Just now you said that it cannot be verified. That means false. Prabhupāda: Acaba de decir que no se puede verificar. Eso significa que es falso.

Śyāmasundara: It cannot be verified if it is true or false. But it can... Śyāmasundara: No se puede verificar si es verdadero o falso. Pero puede...

Prabhupāda: That means doubt. It is doubtful. Prabhupāda: Eso significa duda. Es dudoso.

Śyāmasundara: Just like the proposition, “The sum of the angles of a triangle equals 180 degrees”. Śyāmasundara: Igual que la proposición: “La suma de los ángulos de un triángulo es igual a 180 grados”.

Prabhupāda: That is accepted by the scientists and mathematicians. Prabhupāda: Eso es aceptado por los científicos y los matemáticos.

Śyāmasundara: Yes. That can be said to be a valid proposition or an invalid proposition. Demonstrated. Śyāmasundara: Sí. Se puede decir que es una proposición válida o una proposición inválida. Demostrado.

Prabhupāda: Why invalid? It is valid because all mathematicians, all scientists, they have accepted it. Prabhupāda: ¿Por qué inválida? Es válida porque todos los matemáticos, todos los científicos, la han aceptado.

Śyāmasundara: Yes. It can be demonstrated that it is valid on paper. But it cannot be said that it is true or false by our experiential data. Śyāmasundara: Sí. Se puede demostrar que es válido sobre el papel. Pero no se puede decir que sea verdadera o falsa por nuestros datos experienciales.

Prabhupāda: No. That can be said, it is false, because in this world everything is a temporary manifestation. So this world itself is a temporary manifestation. This big sky and this planet and everything is a temporary manifestation. Prabhupāda: No. Eso puede decirse, es falso, porque en este mundo todo es una manifestación temporal. Así que este mundo mismo es una manifestación temporal. Este gran cielo y este planeta y todo es una manifestación temporal.

Śyāmasundara: So even that law is temporary, that “The sum of the angles equals 180 degrees”? Śyāmasundara: ¿Así que incluso esa ley es temporal, que “La suma de los ángulos es igual a 180 grados”?

Prabhupāda: Sí.

Śyāmasundara: That's only temporary. Śyāmasundara: Eso es sólo temporal.

Prabhupāda: Temporary in this sense: because the existence of this universe is also temporary. So whatever is there is temporary. Prabhupāda: Temporal en este sentido: porque la existencia de este universo también es temporal. Así que todo lo que hay es temporal.

Śyāmasundara: But even when this universe ends, doesn't that law carry on? Śyāmasundara: Pero incluso cuando este universo termina, ¿no continúa esa ley?

Prabhupāda: Just like this waterpot. This waterpot, you can say false or true. False means when it breaks, then it no longer will be waterpot; it becomes earth again. From the earth it is made, and again it becomes earth. Therefore the shape of this waterpot is not false but temporary. That is the right word. It will not remain as earthen pot for very long time. It will break, and when it breaks, it again becomes earth, from which it was made; therefore this shape is temporary. Prabhupāda: Al igual que esta jarra de agua. Esta vasija de agua, puedes decir que es falsa o verdadera. Falso significa que cuando se rompe, entonces ya no será una vasija de agua; se convierte en tierra de nuevo. De la tierra se hace y de nuevo se convierte en tierra. Por lo tanto, la forma de esta vasija de agua no es falsa, sino temporal. Esa es la palabra correcta. No permanecerá como una vasija de tierra durante mucho tiempo. Se romperá, y cuando se rompa, se convertirá de nuevo en tierra, de la que fue hecha; por lo tanto, esta forma es temporal.

Śyāmasundara: That example of the pot, we can verify if it is true or false by our senses. Śyāmasundara: Ese ejemplo del recipiente, podemos verificar si es verdadero o falso por nuestros sentidos.

Prabhupāda: The senses, it is also senses. I am taking it as waterpot, that is I am taking it by my senses. But the shape of the waterpot is temporary. Prabhupāda: Los sentidos, también son sentidos. Lo estoy tomando como una vasija de agua, es decir, lo estoy tomando por mis sentidos. Pero la forma de la vasija de agua es temporal.

Śyāmasundara: That can be proven. Śyāmasundara: Eso se puede probar.

Prabhupāda: Yes. So whatever there is in this world, even this house, this big house, this is also temporary. Prabhupāda: Sí. Así que todo lo que hay en este mundo, incluso esta casa, esta gran casa, también es temporal.

Śyāmasundara: But what about a principle, like “Two plus two equals four”? Śyāmasundara: Pero ¿qué hay de un principio, como “Dos más dos es igual a cuatro”?

Prabhupāda: Principle is truth, but the manifestation is temporary. Principle... Just like earth. Just like we hear from Bhagavad-gītā, bhūmir āpo 'nalo vāyuḥ khaṁ mano buddhir eva ca: (BG 7.4) “This earth, water, fire, air, ether, mind, intelligence, ego, they are My separated energies”. And because it is Kṛṣṇa's energy, and Kṛṣṇa is true, therefore that energy is true. But this interaction of the energy, manifestation of different things out of that energy, that is temporary. Therefore it is called material energy or external energy, temporary manifestation. Prabhupāda: El principio es la verdad, pero la manifestación es temporal. El principio... Al igual que la tierra. Igual que oímos en la Bhagavad-gītā, bhūmir āpo 'nalo vāyuḥ khaṁ mano buddhir eva ca: (BG 7.4) “Esta tierra, el agua, el fuego, el aire, el éter, la mente, la inteligencia, el ego, son Mis energías separadas”. Y como es la energía de Kṛṣṇa y Kṛṣṇa es verdadero, por tanto esa energía es verdadera. Pero esta interacción de la energía, la manifestación de diferentes cosas fuera de esa energía, eso es temporal. Por lo tanto, se llama energía material o energía externa, manifestación temporal.

Śyāmasundara: What about the proposition that “Two plus two equals four”? Śyāmasundara: ¿Qué hay de la proposición de que “Dos más dos es igual a cuatro”?

Prabhupāda: That is also temporary. Prabhupāda: Eso también es temporal.

Śyāmasundara: That disappears when this universe disappears? Śyāmasundara: ¿Eso desaparece cuando este universo desaparece?

Prabhupāda: Yes. When the universe disappears, everything disappears. Who is going to calculate “Two plus two equals four”? Everything is finished. Prabhupāda: Sí. Cuando el universo desaparece, todo desaparece. ¿Quién va a calcular “Dos más dos es igual a cuatro”? Todo está acabado.

Śyāmasundara: The principle does not carry on, despite... Śyāmasundara: El principio no continúa, a pesar de...

Prabhupāda: The principle will carry on when again there will be manifestation. Just like this waterpot, it breaks, it becomes earth, and again from earth we make waterpot. Therefore this principle that the waterpot is made out of earth, that is a fact, but the waterpot as we see, that is temporary. Creation of the waterpot from earth is a fact. Similarly, this material world is a creation out of Kṛṣṇa's external energy. That is a fact. Kṛṣṇa's energy is fact. Kṛṣṇa is fact. Prabhupāda: El principio continuará cuando vuelva a haber manifestación. Al igual que esta vasija de agua, se rompe, se convierte en tierra y de nuevo de la tierra hacemos una vasija de agua. Por lo tanto, este principio de que la vasija de agua está hecha de tierra, es un hecho, pero la vasija de agua, como vemos, es temporal. La creación de la vasija de agua a partir de la tierra es un hecho. Del mismo modo, este mundo material es una creación de la energía externa de Kṛṣṇa. Eso es un hecho. La energía de Kṛṣṇa es un hecho. Kṛṣṇa es un hecho.

Śyāmasundara: What about something that cannot be tangibly seen, like a mathematical calculation or an equation? Śyāmasundara: ¿Qué pasa con algo que no se puede ver tangiblemente, como un cálculo matemático o una ecuación?

Prabhupāda: You cannot see so many things. That does not mean that it does not exist. Your power of seeing is limited. Why you are depending on seeing? Prabhupāda: No puedes ver tantas cosas. Eso no significa que no exista. Tu poder de ver es limitado. ¿Por qué dependes de la visión?

Śyāmasundara: No. I want to take something that we all know, like “Two plus two equals four,” that principle. There's no waterpot or anything visible involved, just a purely abstract principle, “Two plus two equals four”. Śyāmasundara: Quiero tomar algo que todos conocemos, como “Dos más dos es igual a cuatro”, ese principio. No hay ninguna vasija de agua ni nada visible involucrado, sólo un principio puramente abstracto, “Dos más dos es igual a cuatro”.

Prabhupāda: Abstract or concrete, it doesn't matter. What is abstract for you is concrete for other. (break) ...Kṛṣṇa is concrete. Paraṁ satya, actually that is the only truth. So this idea, abstract and concrete, that is relative. Prabhupāda: Abstracto o concreto, no importa. Lo que es abstracto para ti es concreto para otros. (pausa) ...Kṛṣṇa es concreto. Paraṁ satya, en realidad esa es la única verdad. Así que esta idea, abstracta y concreta, es relativa.

Śyāmasundara: Just like the idea, “The sum of the angles of a triangle equal 180 degrees”. Śyāmasundara: Como la idea, “La suma de los ángulos de un triángulo es igual a 180 grados”.

Prabhupāda: This is calculation. Prabhupāda: Esto es un cálculo.

Śyāmasundara: It is calculation, but there's no... Śyāmasundara: Es un cálculo, pero no hay...

Prabhupāda: Relative knowledge, because we cannot know beyond 180 degrees according to your geometrical calculation. But your calculation, everything is imperfect because you are imperfect. So because it is going on, for our purpose we take it as truth. That's all. Prabhupāda: Conocimiento relativo, porque no podemos saber más allá de 180 grados según su cálculo geométrico. Pero su cálculo, todo es imperfecto porque usted es imperfecto. Así que, porque está pasando, para nuestro propósito lo tomamos como verdad. Eso es todo.

Śyāmasundara: It's only working in two planes, or two dimensions. Śyāmasundara: Sólo funciona en dos planos, o dos dimensiones.

Prabhupāda: Just like this body. This body, I can say is false, but suppose somebody kills somebody, he cannot argue that it is a false thing. If it is killed, why the state should by so much anxious about it if it a false? No. Even it is temporary, even if it's false, but it has got temporary use. You cannot disturb that use. Prabhupāda: Igual que este cuerpo. Este cuerpo, puedo decir que es falso, pero supongamos que alguien mata a alguien, él no puede argumentar que es una cosa falsa. Si es asesinado, ¿por qué el Estado debería preocuparse tanto por él si es falso? No. Incluso es temporal, aunque sea falso, pero tiene un uso temporal. No se puede perturbar ese uso.

Śyāmasundara: He says that propositions pertaining to metaphysical realities such as we have been talking about, like the soul, he says they are neither chronological, that is uninformative assertions, neither are they empirical propositions. So it is impossible to demonstrate either their validity or to verify them. Śyāmasundara: Dice que las proposiciones que pertenecen a realidades metafísicas como las que hemos estado hablando, como el alma, dice que no son ni cronológicas, es decir, afirmaciones no informativas, ni son proposiciones empíricas. Por lo tanto, es imposible demostrar su validez o verificarlas.

Prabhupāda: ¿Por qué?

Śyāmasundara: Statements like “the soul,” “I am the soul”. Śyāmasundara: Afirmaciones como “el alma”, “yo soy el alma”.

Prabhupāda: Sí.

Śyāmasundara: We can neither say that is valid or invalid, neither we can say it is... Śyāmasundara: No podemos decir que es válido o inválido, tampoco podemos decir que es...

Prabhupāda: It is valid. It is not invalid, it is valid. You cannot understand it. Try to understand it. It is valid. “I am the soul,” that's a valid proposition. How you can say invalid? Prabhupāda: Es válido. No es inválido, es válido. No puedes entenderlo. Trata de entenderlo. Es válido. “Yo soy el alma”, esa es una proposición válida. ¿Cómo puedes decir que es inválida?

Devānanda: He also says that it cannot be demonstrated also. Devānanda: También dice que no se puede demostrar también.

Prabhupāda: This is demonstration. Demonstration, this is demonstration, that as soon as I go, actually I go (indistinct). That is demonstration. What do you want more demonstration? Prabhupāda: Esto es una demostración. Demostración, esto es demostración, que tan pronto como voy, realmente voy (inaudible). Eso es una demostración. ¿Qué más demostración quieres?

Śyāmasundara: He says we have to know what conditions are required to show that it is true and then satisfy those conditions. So one condition you say is that as soon as the body dies, then there is no more movement. But what is there to prove that the soul has left the body or that there was ever a soul in the body? Śyāmasundara: Dice que tenemos que saber qué condiciones se requieren para demostrar que es verdad y luego satisfacer esas condiciones. Así que una condición que dices es que tan pronto como el cuerpo muere, entonces no hay más movimiento. Pero ¿qué es lo que demuestra que el alma ha abandonado el cuerpo o que alguna vez hubo un alma en el cuerpo?

Prabhupāda: That is the proof. Because the soul takes shelter into the womb of the mother, the father injects the soul - that is the statement of the śāstras - in the womb of the mother, and the mother gives shelter. So the body develops from the womb of the mother. There is conception, pregnancy. That is the proof. Prabhupāda: Esa es la prueba. Porque el alma se refugia en el vientre de la madre, el padre inyecta el alma -esa es la afirmación de los śāstras- en el vientre de la madre, y la madre le da refugio. Así que el cuerpo se desarrolla desde el vientre de la madre. Hay concepción, embarazo. Esa es la prueba.

Śyāmasundara: Ultimately there is nothing to measure, when the body dies, to determine where that soul went. Śyāmasundara: En última instancia no hay nada que medir, cuando el cuerpo muere, para determinar a dónde fue esa alma.

Prabhupāda: Yes. That you can measure by knowledge. Just like Bhagavad-gītā has said, ūrdhvaṁ gacchanti sattva-sthā (BG 14.18). Just like a man has committed murder, killed somebody. He is arrested, he is taken away from your sight, but you can know that he has committed murder, he will be hanged. That's all. You do not require to go there and see that he is hanged. It doesn't require. That is foolishness. If somebody says that “I did not see that the man was arrested,” that's all right, but “I did not see that he was hanged. I cannot believe it,” no. You believe or not believe, it is a fact. Prabhupāda: Sí. Eso se puede medir por el conocimiento. Al igual que la Bhagavad-gītā ha dicho, ūrdhvaṁ gacchanti sattva-sthā (BG 14.18). Igual que un hombre ha cometido un asesinato, ha matado a alguien. Se le arresta, se le quita de la vista, pero puedes saber que ha cometido un asesinato, será colgado. Eso es todo. No es necesario que vayas allí y veas que lo cuelgan. No lo requiere. Eso es una tontería. Si alguien dice que “no vi que el hombre fuera arrestado”, está bien, pero “no vi que fuera colgado. No puedo creerlo”, no. Creas o no creas, es un hecho.

Śyāmasundara: So what he is saying is that because you can't see the soul after it leaves the body, therefore we cannot say if the soul exists or does not exist. Śyāmasundara: Así que lo que está diciendo es que como no se puede ver el alma después de que deja el cuerpo, por lo tanto, no podemos decir si el alma existe o no existe.

Prabhupāda: But why does he believe of his eyes so much? Why does he not accept that his eyes are so imperfect that he cannot see the soul? Prabhupāda: ¿Pero por qué cree tanto en sus ojos? ¿Por qué no acepta que sus ojos son tan imperfectos que no puede ver el alma?

Śyāmasundara: Either directly or indirectly he says that we have to be able to prove... Śyāmasundara: Directa o indirectamente dice que tenemos que ser capaces de probar...

Prabhupāda: No. The same example, just like a man has committed murder and he is arrested and taken away. So others, they know that this man will be hanged. And one was, “Oh, I have not seen, so how he is hanged?” But that is foolishness. The state law says that if a man has committed murder he will be hanged. So you have to see through the law, not with your eyes. The nonsense eyes, what can they see? So see through knowledge, through books. Prabhupāda: No. El mismo ejemplo, como un hombre que ha cometido un asesinato y es arrestado y llevado. Entonces otros, saben que este hombre será colgado. Y uno dice: “Oh, yo no he visto, así que, ¿cómo es colgado?” Pero eso es una tontería. La ley estatal dice que si un hombre ha cometido un asesinato será colgado. Así que tienes que ver a través de la ley, no con tus ojos. Los ojos sin sentido, ¿qué pueden ver? Así que ve a través del conocimiento, a través de los libros.

Śyāmasundara: So our ultimate verification does not rest with our senses but with the authoritative... Śyāmasundara: Así que nuestra última verificación no descansa en nuestros sentidos sino en la autoridad...

Prabhupāda: Yes. Authoritative knowledge, that is real seeing. That is real seeing. Just like we have not seen Kṛṣṇa, take for example. Then all we are fools and rascals, that we are after Kṛṣṇa? People may say that “You have not seen Kṛṣṇa. Why you are after so much, Kṛṣṇa?” They can say. But then you are all set of fools. Does it mean that we are all set of fools? Then how we have seen Kṛṣṇa? “Prabhupāda”: Sí. El conocimiento autorizado, eso es ver realmente. Eso es ver de verdad. Al igual que no hemos visto a Kṛṣṇa, por ejemplo. Entonces ¿todos somos tontos y bribones, que estamos tras de Kṛṣṇa? La gente puede decir que “Usted no ha visto Kṛṣṇa. ¿Por qué usted está buscando tanto a Kṛṣṇa?” Ellos pueden decir. Pero entonces todos ustedes son un conjunto de tontos. ¿Significa que todos somos un conjunto de tontos? Entonces ¿cómo hemos visto a Kṛṣṇa?

Śyāmasundara: Wittgenstein, in that respect he answers that these metaphysical or mystical ideas, even though they are not expressed in words, can be felt or appreciated without knowing whether it is true. Śyāmasundara: Wittgenstein, al respecto responde que estas ideas metafísicas o místicas, aunque no se expresen con palabras, se pueden sentir o apreciar sin saber si es verdad.

Prabhupāda: No. That is knowing. To know through authorities, that is knowing. That is real knowing. That is the process of Vedic knowledge: to know through the authorities. The same example: if somebody is asking, “Who is my father?” then he has to know through the authority of mother; otherwise there is no other way. So therefore to know through authority is perfect knowledge. Prabhupāda: No. Eso es saber. Conocer a través de las autoridades, eso es conocer. Ese es el verdadero conocimiento. Ese es el proceso del conocimiento védico: conocer a través de las autoridades. El mismo ejemplo: si alguien pregunta: “¿Quién es mi padre?”, entonces tiene que saber a través de la autoridad de la madre; de lo contrario, no hay otra manera. Por lo tanto, conocer a través de la autoridad es el conocimiento perfecto.

Śyāmasundara: These modern scientists, they fall back on that idea that “Well, I accept that there is something mystical or metaphysical, but because I don't know it is truth, still I appreciate it”. Or “It cannot be experienced, we must consign it to science”. Śyāmasundara: Estos científicos modernos, vuelven a caer en esa idea de que “Bueno, acepto que hay algo místico o metafísico, pero como no sé qué es la verdad, aun así lo aprecio”. O “No se puede experimentar, debemos consignarlo a la ciencia”.

Prabhupāda: Truth is truth. Either we appreciate or not appreciate, it does not matter. Truth is truth. Prabhupāda: La verdad es la verdad. Si apreciamos o no apreciamos, no importa. La verdad es la verdad.

Śyāmasundara: So they fall back on kind of a blind faith... Śyāmasundara: Así que se apoyan en una especie de fe ciega...

Prabhupāda: But you are in blind faith. Those who do not accept the authorities, they are in blind faith. Just like one who does not know that what is soul, he is in blind faith, accepting this body as self. He is in blind faith. Prabhupāda: Pero usted tiene una fe ciega. Aquellos que no aceptan a las autoridades, tienen una fe ciega. Al igual que el que no sabe qué es el alma, está en la fe ciega, aceptando este cuerpo como el yo. Tiene una fe ciega.

Śyāmasundara: He has no real evidence that my self is the body either. Śyāmasundara: Tampoco tiene pruebas reales de que mi yo sea el cuerpo.

Prabhupāda: He is blind, because it is not the fact. The evidence is there, but he is in blind faith. The whole world is working in blind faith - “I am Pakistani,” “I am Hindustani,” “I am American,” “I am Englishman”. Simply bodily identification. The whole world is a set of fools only. That's all. That is stated in the śāstras: yasyātma-buddhiḥ kuṇape tri-dhātuke (SB 10.84.13). Anyone who accepts this bag of three dhātus, kapha, pitta, vāyu, as self, he is an ass. Prabhupāda: Está ciego, porque no es el hecho. La evidencia está ahí, pero él está en la fe ciega. El mundo entero está trabajando en la fe ciega - “Yo soy pakistaní”, “Yo soy hindú”, “Yo soy americano”, “Yo soy inglés”. Simplemente una identificación corporal. El mundo entero es un conjunto de tontos solamente. Eso es todo. Eso se afirma en las śāstras: yasyātma-buddhiḥ kuṇape tri-dhātuke (SB 10.84.13). Cualquiera que acepte esta bolsa de tres dhātus, kapha, pitta, vāyu, como el yo, es un asno.

Śyāmasundara: He says that atomic propositions, or the components of compound propositions, depend for their validity upon the reliability with which they accurately picture atomic facts. In other words, suppose there is some proposition that this ring is gold. This proposition is part of a compound proposition which tells where the ring came from, how it was originated, who wore it, so many other facts. But only you take one proposition, “this ring is gold,” he said this proposition depends upon the reliability with which it accurately pictures the facts, if it is true or false. That statement, “this ring is gold,” it must determine how accurately it pictures the facts before we can say if it is valid or invalid proposition. Śyāmasundara: Dice que las proposiciones atómicas, o los componentes de las proposiciones compuestas, dependen para su validez de la fiabilidad con la que ilustran con precisión los hechos atómicos. En otras palabras, supongamos que hay una proposición de que este anillo es de oro. Esta proposición forma parte de una proposición compuesta que dice de dónde procede el anillo, cómo se originó, quién lo llevaba, y tantos otros hechos. Pero sólo si se toma una proposición, “este anillo es de oro”, dijo que esta proposición depende de la fiabilidad con la que retrata con precisión los hechos, si es verdadera o falsa. Esa afirmación, “este anillo es de oro”, debe determinar la precisión con la que retrata los hechos antes de que podamos decir si es una proposición válida o inválida.

Prabhupāda: Suppose I say it is gold. What he will say? What is his proposition? Prabhupāda: Supongamos que digo que eso es oro. ¿Qué dirá él? ¿Cuál es su propuesta?

Śyāmasundara: He'll say that first of all you must give us a list of conditions to determine why it is gold, under what conditions it is gold. Śyāmasundara: Dirá que, en primer lugar, debes darnos una lista de condiciones para determinar por qué es oro, en qué condiciones es oro.

Prabhupāda: That is everything. That he is speaking also, that is another condition. Prabhupāda: Eso es todo. Que esté hablando también, esa es otra condición.

Śyāmasundara: There must be certain conditions met before... Śyāmasundara: Deben cumplirse ciertas condiciones antes de...

Prabhupāda: But how he is speaking is also fact, that he is speaking under certain conditions. Everything in this material world, that is on condition. So his philosophizing is also under condition. So everything is conditioned. Why does he not understand first of all himself, instead of trying to understand what is gold? Everything is conditioned. Prabhupāda: Pero la forma en que habla también es un hecho, que habla bajo ciertas condiciones. Todo en este mundo material, está bajo condición. Así que su filosofar también está bajo condición. Así que todo está condicionado. ¿Por qué no se entiende primero a sí mismo, en lugar de tratar de entender lo que es oro? Todo está condicionado.

Śyāmasundara: If we listed for some conditions that it must weigh a certain amount, it must have a certain color, it must have a certain texture, like that... Śyāmasundara: Si enumeramos por algunas condiciones que debe pesar cierta cantidad, debe tener cierto color, debe tener cierta textura, así...

Prabhupāda: That is already there. Those who are chemists, they know what is the characteristics of gold. That is already there, recorded. So what does he want? Prabhupāda: Eso ya está ahí. Aquellos que son químicos, saben cuáles son las características del oro. Eso ya está ahí, registrado. Entonces, ¿qué es lo que quiere?

Śyāmasundara: This is part of his system for analyzing what is true or untrue. Śyāmasundara: Esto es parte de su sistema para analizar lo que es verdadero o falso.

Prabhupāda: That analysis is there. It may not be with me, it may not be with you, but it is already there. But what he will do with that analysis? What is his aim? Prabhupāda: Ese análisis está ahí. Puede que no esté conmigo, puede que no esté con usted, pero ya está ahí. Pero, ¿qué hará él con ese análisis? ¿Cuál es su objetivo?

Śyāmasundara: Well, we can satisfy his conditions and then determine if it is true that this ring is gold. Śyāmasundara: Bueno, podemos satisfacer sus condiciones y luego determinar si es cierto que este anillo es de oro.

Prabhupāda: Yes. There are so many conditions. After, at the end, the conditions come to atom, atomic theory. But the atom is also conditioned, aṇḍāntara-sthaṁ paramāṇu cayāntara-stham. Kṛṣṇa is within the atom also; therefore the atom is not absolute or independent. Therefore Kṛṣṇa is the ultimate fact. Prabhupāda: Sí. Hay muchas condiciones. Después, al final, las condiciones llegan al átomo, a la teoría atómica. Pero el átomo también está condicionado, aṇḍāntara-sthaṁ paramāṇu cayāntara-stham. Kṛṣṇa está dentro del átomo también; por lo tanto, el átomo no es absoluto o independiente. Por tanto, Kṛṣṇa es el hecho último.

- īśvaraḥ paramaḥ kṛṣṇaḥ

- sac-cid-ānanda-vigrahaḥ

- anādir ādir govindaḥ

- sarva-kāraṇa-kāraṇam

- (BS 5.1)

That we have know, that He is the cause of all causes. Eso hemos conocido, que Él es la causa de todas las causas.

Śyāmasundara: So, for instance, the ring may be gold under one set of conditions... Śyāmasundara: Así, por ejemplo, el anillo puede ser de oro bajo un conjunto de condiciones...

Prabhupāda: Yes. It is gold under certain conditions, but the original cause is Kṛṣṇa. Everything. Under certain conditions something is wood, something is gold, something is metal, something is this, something is... These are different conditions. I am also conditioned. Under certain conditions I am talking that “I am human being”. Otherwise animal, he is under certain conditions, he is an animal. So everyone is under conditions. Who is not under conditions? Everything is under conditions. Therefore this world is called conditioned world or relative world. Nothing is absolute. Prabhupāda: Sí. Es oro bajo ciertas condiciones, pero la causa original es Kṛṣṇa. Todo. Bajo ciertas condiciones algo es madera, algo es oro, algo es metal, algo es esto, algo es... Son condiciones diferentes. Yo también estoy condicionado. Bajo ciertas condiciones estoy hablando de que “soy un ser humano”. Si no, el animal, bajo ciertas condiciones, es un animal. Así que todo el mundo está bajo condiciones. ¿Quién no está bajo condiciones? Todo está bajo condiciones. Por lo tanto, este mundo es llamado mundo condicionado o mundo relativo. Nada es absoluto.

Śyāmasundara: He says that a proposition is a... Śyāmasundara: Dice que una proposición es...

Prabhupāda: It is gold, gold means it is a metal, a combination of metals. There are eight types of metals, and gold is combination of tin, copper and mercury. Prabhupāda: Es oro, oro significa que es un metal, una combinación de metales. Hay ocho tipos de metales, y el oro es una combinación de estaño, cobre y mercurio.

Śyāmasundara: There is a basic element-gold. Śyāmasundara: Hay un elemento básico: el oro.

Prabhupāda: Not basic. It is a combination of different elements, different metals. Prabhupāda: No es básico. Es una combinación de diferentes elementos, diferentes metales.

Śyāmasundara: According to the chemists, there are 108 basic elements, and gold is one of them. Śyāmasundara: Según los químicos, hay 108 elementos básicos y el oro es uno de ellos.

Prabhupāda: That may be, but I say that what you call gold is a combination of other metals. So gold, this is not absolute. This is relative. Because other metals have combined together, it is now known as gold. Similarly, the whole world is combination of different material elements, and the gross elements are this earth, water, fire, air, ether. Prabhupāda: Puede ser, pero yo digo que lo que usted llama oro es una combinación de otros metales. Así que el oro, esto no es absoluto. Es relativo. Porque otros metales se han combinado juntos, ahora se conoce como oro. Del mismo modo, el mundo entero es una combinación de diferentes elementos materiales y los elementos brutos son la tierra, el agua, el fuego, el aire y el éter.

Śyāmasundara: What about..., they say that there is a basic atom called a hydrogen atom. Śyāmasundara: ¿Qué hay de...?, dicen que hay un átomo básico llamado átomo de hidrógeno.

Prabhupāda: Whatever you will call it, it is also matter. The minute particles are matter. That's all. Prabhupāda: Lo llamen como lo llamen, también es materia. Las partículas diminutas son materia. Eso es todo.

Śyāmasundara: That's right. Inside these molecules there are atoms, and inside the atoms there are more particles, and it goes on, smaller and smaller. Śyāmasundara: Así es. Dentro de estas moléculas hay átomos, y dentro de los átomos hay más partículas, y así sucesivamente, cada vez más pequeñas.

Prabhupāda: Yes. These are all matter. Prabhupāda: Sí. Todo esto es materia.

Śyāmasundara: He says that a proposition is a picture of reality, a picture is a model of reality, a picture is a fact, the world is a totality of facts, the totality of true thoughts is a picture of the world. Śyāmasundara: Dice que una proposición es una imagen de la realidad, una imagen es un modelo de la realidad, una imagen es un hecho, el mundo es una totalidad de hechos, la totalidad de pensamientos verdaderos es una imagen del mundo.

Prabhupāda: Totality of not facts, that is a combination of gross matter, combination of gross and subtle matter. But this gross and subtle matter are projection of Kṛṣṇa's energy. Therefore totalities, they can be said Kṛṣṇa's external energy. And because Kṛṣṇa's energy, the energy and energetic, sometimes separated, sometimes mixed up; when separated, it manifests as something creation; when it is mixed up, the energy is no longer - it is merged into the energetic. Therefore Kṛṣṇa is the ultimate cause. Prabhupāda: La totalidad de no hechos, eso es una combinación de materia burda, combinación de materia burda y sutil. Pero esta materia burda y sutil son proyección de la energía de Kṛṣṇa. Por lo tanto, las totalidades, se puede decir la energía externa de Kṛṣṇa. Y porque la energía de Kṛṣṇa, la energía y el energético, a veces se separan, a veces se mezclan; cuando se separan, se manifiestan como creación de algo; cuando se mezclan, la energía ya no está - se funde en el energético. Por lo tanto, Kṛṣṇa es la causa última.

Śyāmasundara: So the picture of reality is always changing? There are no set combinations? Śyāmasundara: ¿Entonces la imagen de la realidad siempre está cambiando? No hay combinaciones fijas?

Prabhupāda: Reality is not changing. The combination of different energies is changing. Reality is not changing. Prabhupāda: La realidad no está cambiando. La combinación de diferentes energías está cambiando. La realidad no está cambiando.

Śyāmasundara: So true thoughts are not changing. Śyāmasundara: Así que los pensamientos verdaderos no cambian.

Prabhupāda: Reality is Kṛṣṇa, but Kṛṣṇa has got unlimited number of energies, so the combination of different energy is making some manifestation and they are changing. Prabhupāda: La realidad es Kṛṣṇa, pero Kṛṣṇa tiene un número ilimitado de energías, así que la combinación de diferentes energías está haciendo alguna manifestación y están cambiando.

Śyāmasundara: He says that the totality of true thoughts is the picture of the world. So that picture does not change. The true thoughts do not change. So the world is not actually... Śyāmasundara: Dice que la totalidad de los pensamientos verdaderos es la imagen del mundo. Así que esa imagen no cambia. Los pensamientos verdaderos no cambian. Así que el mundo no es realmente...

Prabhupāda: Yes. Conservation of energy. Everything rests ultimately in energy, and the energy ultimately rests in Kṛṣṇa. Therefore we say that everything ultimately rests in Kṛṣṇa. Kṛṣṇa is the ultimate cause, ahaṁ sarvasya prabhavaḥ mattaḥ sarvaṁ pravartate: (BG 10.8) “I am the cause of everything”. Prabhupāda: Sí. Conservación de la energía. Todo descansa en última instancia en la energía y la energía descansa en última instancia en Kṛṣṇa. Por lo tanto, decimos que todo descansa en última instancia en Kṛṣṇa. Kṛṣṇa es la causa última, ahaṁ sarvasya prabhavaḥ mattaḥ sarvaṁ pravartate: (BG 10.8) “Yo soy la causa de todo”.

Śyāmasundara: He says that language is a picture of reality-language, words, a picture of reality. Just like we are speaking now. We are making pictures of reality as we speak with our language, with our words. Do these words have more content in themselves, or are they simply pictures of reality? Śyāmasundara: Dice que el lenguaje es una imagen de la realidad-el lenguaje, las palabras, una imagen de la realidad. Al igual que estamos hablando ahora. Estamos haciendo imágenes de la realidad mientras hablamos con nuestro lenguaje, con nuestras palabras. ¿Tienen estas palabras más contenido en sí mismas, o son simplemente imágenes de la realidad?

Prabhupāda: Language is a sort of expression to understand reality. Language is not reality. Prabhupāda: El lenguaje es una especie de expresión para entender la realidad. El lenguaje no es la realidad.

Śyāmasundara: Yes. He says that propositions or statements of ideas provide merely the form, telling us not what things are but how they are, but only how they are. Śyāmasundara: Sí. Dice que las proposiciones o enunciados de ideas proporcionan meramente la forma, diciéndonos no lo que las cosas son sino cómo son, pero sólo cómo son.

Prabhupāda: As well as what they are. If they are how they are, then what they are can also be explained. Prabhupāda: Así como lo que son. Si son como son, entonces también se puede explicar lo que son.

Śyāmasundara: Just like if I describe this picture, I cannot really say what it is, but only how it is, what it is like, how it is. Śyāmasundara: Al igual que si describo esta imagen, no puedo decir realmente lo que es, sino sólo cómo es, cómo es, cómo es.

Prabhupāda: What is the difference, “how it is” and “what it is”? What is the difference? It is simply jugglery of words. If I can say how it is, I can say what it is. Prabhupāda: ¿Cuál es la diferencia, “cómo es” y “qué es”? ¿Cuál es la diferencia? Es simplemente un juego de palabras. Si puedo decir cómo es, puedo decir qué es.

Śyāmasundara: He says what it is can only be experienced by the other senses - by seeing it, touching it. Śyāmasundara: Dice que lo que es sólo puede ser experimentado por los otros sentidos - viéndolo, tocándolo.

Prabhupāda: In this sense, how it is, of course it can be explained like that. Ultimately, what it is means just like this gold, I said that how it is - a combination of other metals is gold, that is how it is. But what it is, that we have to research further. Just like how it is - a combination of copper, tin and mercury. Now, then what it is, we will have to make inquiry wherefrom this mercury comes, wherefrom this tin comes, wherefrom the copper comes. That is what it is. Therefore Vedic language it is sarvaṁ khalv idaṁ brahma: “Everything is Brahman”. That is what it is. Prabhupāda: En este sentido, cómo es, por supuesto que se puede explicar así. En última instancia, lo que es significa igual que este oro, he dicho que cómo es - una combinación de otros metales es oro, así es como es. Pero lo que es, eso tenemos que investigar más. Al igual que cómo es - una combinación de cobre, estaño y mercurio. Ahora, entonces lo que es, tendremos que hacer la investigación de dónde viene este mercurio, de dónde viene este estaño, de dónde viene el cobre. Eso es lo que es. Por lo tanto, el lenguaje védico es sarvaṁ khalv idaṁ brahma: “Todo es Brahman”. Eso es lo que es.

Śyāmasundara: (laughing) So we can explain how it is molded into different ways. Śyāmasundara: (riendo) Así podemos explicar cómo se moldea en diferentes formas.

Prabhupāda: That is how it is, how it has become gold. But ultimately it is Brahman, sarvaṁ khalv idaṁ brahma. Everything is Brahman. Prabhupāda: Así es, como se ha convertido en oro. Pero en última instancia es Brahman, sarvaṁ khalv idaṁ brahma. Todo es Brahman.

Śyāmasundara: He says that therefore most philosophical propositions are not false, but they are devoid of sensory facts, of sense content; therefore they are nonsensical. Śyāmasundara: Dice que, por lo tanto, la mayoría de las proposiciones filosóficas no son falsas, pero están desprovistas de hechos sensoriales, de contenido sensorial; por lo tanto, no tienen sentido.

Prabhupāda: Therefore he is also nonsensical. Prabhupāda: Por lo tanto, también es un sinsentido.

Śyāmasundara: He comes to that. (laughter) When a genuine proposition... Śyāmasundara: Llega a eso. (Risas) Cuando una proposición genuina...

Prabhupāda: Then why is he after so much nonsensical things? Just to show he's... Prabhupāda: Entonces, ¿por qué va detrás de tantas cosas sin sentido? Sólo para demostrar que es...

Śyāmasundara: In order to find out what is a genuine proposition, he says that a genuine proposition presents the sense content and shows how things stand if it is true. Śyāmasundara: Para saber qué es una proposición genuina, dice que una proposición genuina presenta el contenido de sentido y muestra cómo están las cosas si es verdad.

Prabhupāda: This is sense content, that sarvaṁ khalv, “Everything is Brahman”. Everything is Brahman. Prabhupāda: Este es el contenido de los sentidos, ese sarvaṁ khalv, “Todo es Brahman”. Todo es Brahman.

Śyāmasundara: But how does that give us sense content? What does that mean to my sense observations? Śyāmasundara: Pero ¿cómo nos da eso contenido sensorial? ¿Qué significa eso para mis observaciones sensoriales?

Devānanda: Isn't there a way... There is a way of perceiving that everything is Brahman. It can be perceived. We cannot perceive it now, but it can be perceived. Devānanda: No hay una manera... Hay una forma de percibir que todo es Brahman. Se puede percibir. No podemos percibirlo ahora, pero puede ser percibido.

Prabhupāda: But the true knowledge, that ultimately Brahman is the ultimate cause. So Brahman has got different energies, and the multiple energies, they are combined together, and they manifest in different phases. Therefore Brahman is the cause of all causes. That is the Vedānta-sūtra, janmādy asya yataḥ (SB 1.1.1). Brahman means wherefrom everything is emanating. Prabhupāda: Pero el verdadero conocimiento, que en última instancia Brahman es la causa última. Así que Brahman tiene diferentes energías y las múltiples energías, se combinan juntas y se manifiestan en diferentes fases. Por lo tanto, Brahman es la causa de todas las causas. Eso es el Vedānta-sūtra, janmādy asya yataḥ (SB 1.1.1). Brahman significa de donde todo está emanando.

Śyāmasundara: But this statement, “Everything is Brahman,” that seems to me devoid of sensory fact, of sense content. Therefore he says it is nonsensical, because I cannot experience it as a sensory experience. How does that have sense content, that statement? Śyāmasundara: Pero esta afirmación, “Todo es Brahman”, me parece carente de hecho sensorial, de contenido sensorial. Por eso dice que no tiene sentido, porque no puedo experimentarlo como una experiencia sensorial. ¿Cómo puede tener contenido sensorial esa afirmación?

Prabhupāda: That means whatever does not come through his senses, that is not true. Prabhupāda: Eso significa que lo que no llega a través de sus sentidos, no es verdad.

Śyāmasundara: No. But whatever cannot be experienced is not true. Śyāmasundara: No. Pero lo que no puede experimentarse no es cierto.

Prabhupāda: Experience means by sense experience. That means whatever is not under direct perception, sense experience, that is false. Prabhupāda: Experiencia significa experiencia sensorial. Eso significa que todo lo que no está bajo la percepción directa, la experiencia sensorial, es falso.

Śyāmasundara: Either direct or indirect. But how can I experience that statement that “Everything is Brahman”? Śyāmasundara: Ya sea directa o indirectamente. Pero, ¿cómo puedo experimentar esa afirmación de que “Todo es Brahman”?

Prabhupāda: Indirect is there. Just like we accept that everything has got some cause. So I am a person; the cause is my person father, and his father is also person. Similarly, the ultimate father, the original father, although I have not seen, I cannot sense perceive, still, I must conclude that He is a person. Prabhupāda: Lo indirecto está ahí. Al igual que aceptamos que todo tiene alguna causa. Así que yo soy una persona; la causa es mi padre persona, y su padre también es persona. Similarmente, el padre último, el padre original, aunque no lo he visto, no puedo percibirlo, aun así, debo concluir que Él es una persona.

Śyāmasundara: But I think behind your statement “Everything is Brahman,” there are also statements which show the person how to experience Brahman. Śyāmasundara: Pero creo que detrás de su afirmación “Todo es Brahman”, hay también afirmaciones que muestran a la persona cómo experimentar Brahman.

Prabhupāda: This is Brahman. Brahman means the greatest. Greatest. Prabhupāda: Esto es Brahman. Brahman significa lo más grande. Lo más grande.

Śyāmasundara: But when you say “Everything is Brahman,” you are also willing to include another set of propositions which show how to experience Brahman, how one can experience this fact, “Everything is Brahman”. Śyāmasundara: Pero cuando usted dice “Todo es Brahman”, también está dispuesto a incluir otro conjunto de proposiciones que muestran cómo experimentar Brahman, cómo se puede experimentar este hecho, “Todo es Brahman”.

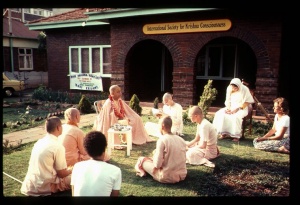

Prabhupāda: That is not very difficult. Just like this International Society. Originally I started, so in any center, I am there. I am there. My photograph is there, I am there, accepting, Bhaktivedanta Swami. So personally I am not there, but I still am there by my expansion of energy. So similarly, Kṛṣṇa is the original Brahman. Whatever we see, we perceive, experience, it's all Kṛṣṇa's expansion of energy. That's all. Prabhupāda: Eso no es muy difícil. Al igual que esta Sociedad Internacional. Originalmente yo empecé, así que en cualquier centro, estoy allí. Estoy allí. Mi fotografía está allí, estoy allí, aceptando, Bhaktivedanta Swami. Así que personalmente no estoy allí, pero todavía estoy allí por mi expansión de energía. Así que, de manera similar, Kṛṣṇa es el Brahman original. Todo lo que vemos, percibimos, experimentamos, es la expansión de energía de Kṛṣṇa. Eso es todo.

Śyāmasundara: His attack, then, is not upon your statement “Everything is Brahman,” because you are also proposing other propositions which show how to experience that everything is Brahman. His attack is upon philosophy that is empty or devoid of sense contact. Śyāmasundara: Su ataque, entonces, no es sobre su declaración “Todo es Brahman”, porque usted también propone otras proposiciones que muestran cómo experimentar que todo es Brahman. Su ataque es a la filosofía que está vacía o desprovista de contacto con los sentidos.

Prabhupāda: That is not empty. Suppose... Prabhupāda: Eso no está vacío. Supongamos...

Devotee: He would say that if we can demonstrate that everything is Brahman, then it is not empty philosophy; then it is factual philosophy. Devoto: Él diría que si podemos demostrar que todo es Brahman, entonces no es una filosofía vacía; entonces es una filosofía factual.